Photo: Intelligencer; Photo: Getty Images

For a good long time, if you wanted to watch a major news event unfold online, your best bet was probably Twitter. It offered a flawed and partial view of what was going on during, say, a major hurricane, when official warnings and on-the-ground reports from professionals and amateurs had to contend with shark hoaxes and conspiracy theories, but it was clearly a useful resource. During Hurricane Sandy, I remember it as a source of local information and an outlet for my own local reporting. Online, at least, it was where the bigger picture came into focus early: The storm had been huge — worse than expected — and entire neighborhoods had been devastated.

It was one of those small golden eras you didn’t realize you were in, in part because it didn’t seem that great but mostly because you had no idea how much worse things would eventually get. For most of the 2010s, sources posting on Twitter were relatively diverse and, while frequently shitty and even malign, easy enough to verify or dismiss. News professionals treated Twitter as a second, unpaid job. Local, state, and national officials treated it as a broadcast system. Locals and eyewitnesses understood that it was an efficient way to get the word out. People with large followings worked as aggregators, sharing and amplifying what they were seeing in their feeds. It was also fast. In 2011, I saw posts about an earthquake in D.C. a few seconds before I felt my office chair wiggle in Manhattan. Twitter was always a mess, but it had something. In the right circumstances, it could actually be useful.

If, yesterday, you found yourself in the path of Hurricane Milton or were concerned about friends or family in Florida, you might have logged on, out of habit, to see what was happening. You would have encountered something worse than useless. On a functional level, the app is now centered on the algorithmic “For You” page, a sloshing pool of engagement chum in which a Category 5 hurricane gathering power in the Gulf is left to compete with videos of car crashes, posts from Elon Musk–adjacent right-wing maniacs, and a dash of whatever poorly targeted interest-based bait the platform thinks you might engage with, all collected from the past couple weeks. In this feed, paid blue checks get the most visibility, which is exactly what you don’t want in an emergency, in part because of the sorts of people who choose to subscribe to X — the sorts of people who, like the site’s owner, see major storms primarily as an opportunity to tell lies about people they hate — but just as much because of the people who don’t: local reporters and meteorologists; municipal services, fire and police departments, schools, relief organizations, and regular people who find themselves in the middle of a serious situation. The chronological “Following” feed is diminished as well. People have left. The platform’s norms around sharing and re-sharing good or valuable information have collapsed. There’s still something happening under the surface on X, and it maintains some functionality as a tool for sharing and gathering unique and scarce information from real people who otherwise might not get heard (most vividly over the last year, it has been, with TikTok, a vital source of on-the-ground reporting and testimony from Gaza). But it’s massively diminished and getting worse. It’s next update, which will base Blue-check creator payouts on how much engagement they get from other Blue-check creators, is, under current circumstances, will function as something close to an in-kind donation to the campaign to elect Donald J. Trump.)

Many accounts of how Elon Musk changed Twitter contain, or are at least motivated by, a small and unflattering sense of personal loss. It was, among other things, the social network of the public-facing elites, which is what made it both vexing and attractive to people like Musk, who bought the place where his critics, competitors, regulators, fans, investors, and short-sellers liked to post and turned it into a sort of platform-scale Mar-a-lago. In any case, that’s between the old blue checks and the new ones. The one-two punch of Helene, where X was primarily a source of FEMA conspiracy theories, and Milton, where it was about as useful as Threads, highlighted what’s actually been lost here. If you opened X this morning to see what happened in Florida overnight — a reasonable behavior just a few years ago — you might not have found much in your feeds. As Max Read pointed out, if at any point on Thursday morning you tapped the highlighted X topic for Milton, displayed prominently on the app and site, you’d be shown three video streams from Ron DeSantis and… nothing else.

This wouldn’t be such a big deal if the rest of the internet hadn’t become so strangely useless for following breaking news, but it has. Like X, every major social media platform has emphasized algorithmic TikTok-style distribution, moving away from chronological follower-based feeds to endless streams of vertical video from friends and strangers alike, which has the secondary effect of disincentivizing people from posting with real-time distribution in mind. The old instinct to check your feeds during a news event seems sort of silly at the moment. Where are you looking? TikTok? Instagram? Again, you would have encountered a bunch of stupid bullshit on Twitter before the storm bearing down on you made landfall, but along the way, you might have also gotten credible advice to evacuate and links to resources that might tell you where.

For breaking news, Google search is as useless as it’s ever been, which is sort of counterintuitive given its insistence on showing searches things that were published recently (the problem is that most of these things are borderline spam). Facebook is cooked unless you’re in just the right highly moderated local Groups. Major news organizations are all doing liveblogs again, which is nice, but they’re also all doing paywalls again. Local news organizations are conspicuously understaffed for situations like this but do vital work, and TV stations mostly stream now. The lesson at the end of Silicon Valley’s big long new media adventure, in 2024, is that I guess you should probably just tune into the local affiliate. It’s live!

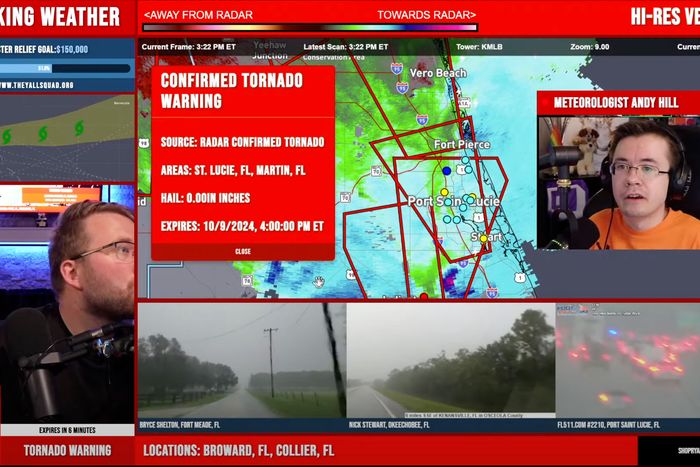

Photo: Ryan Hall Y’all/YouTube

The surprisingly useful resource I found last night, as someone concerned about Milton’s path from afar, was actually a YouTube stream run by an internet personality named Ryan Hall (channel name Ryan Hall, Y’all). The presentation was basic but professional, and the broadcast drew on amateur storm chasers, local sources, and a professional meteorologist. Like a local news broadcast, it was occasionally sensational but basically civic-minded, tracking tornado sightings and paths, repeating official warnings, and passing along standard advice about evacuation, dealing with high winds, and flooding; unlike a local news broadcast, it didn’t worry so much about format or aesthetic convention. It was long, with stretches of silence and moments of chaos, but comprehensive. Along with the team running the stream, hundreds of thousands of live viewers contributed links of their own — some posted and otherwise lost on X — acting as a sort of collective replacement for, and improvement on, a For You algorithm. It was, to someone over the age of 30, a little strange and jarring, and I wouldn’t say the streaming platforms were going too far out of their way to bring the best streamers to their users’ attention. But it was pretty useful and not that hard to find! And one of a few similar operations. The live internet doesn’t belong to X anymore, or even social media, at least as it’s been defined for the last 20 years. It belongs to the streamers.