China hawks in the United States have made what amounted to a Faustian pact with President Donald Trump. Anxious that Beijing’s power was surpassing Washington’s and critical of Democrats such as former President Joe Biden for failing to turn it back, Trump seemed to be the best option for a more robust approach to China. But after the whirlwind start of the new administration, that bargain already looks shaky, raising questions about whether Trump’s much-anticipated pivot to a tougher China policy will instead turn out to be a geopolitical win for Beijing.

Trump’s approach presents a conundrum. On the one hand, he has appointed serious China hawks to important positions, including at the National Security Council, the State Department, and the Defense Department. This team has been crafting the elements of a more competitive approach—albeit with some degree of continuity with Biden’s team.

China hawks in the United States have made what amounted to a Faustian pact with President Donald Trump. Anxious that Beijing’s power was surpassing Washington’s and critical of Democrats such as former President Joe Biden for failing to turn it back, Trump seemed to be the best option for a more robust approach to China. But after the whirlwind start of the new administration, that bargain already looks shaky, raising questions about whether Trump’s much-anticipated pivot to a tougher China policy will instead turn out to be a geopolitical win for Beijing.

Trump’s approach presents a conundrum. On the one hand, he has appointed serious China hawks to important positions, including at the National Security Council, the State Department, and the Defense Department. This team has been crafting the elements of a more competitive approach—albeit with some degree of continuity with Biden’s team.

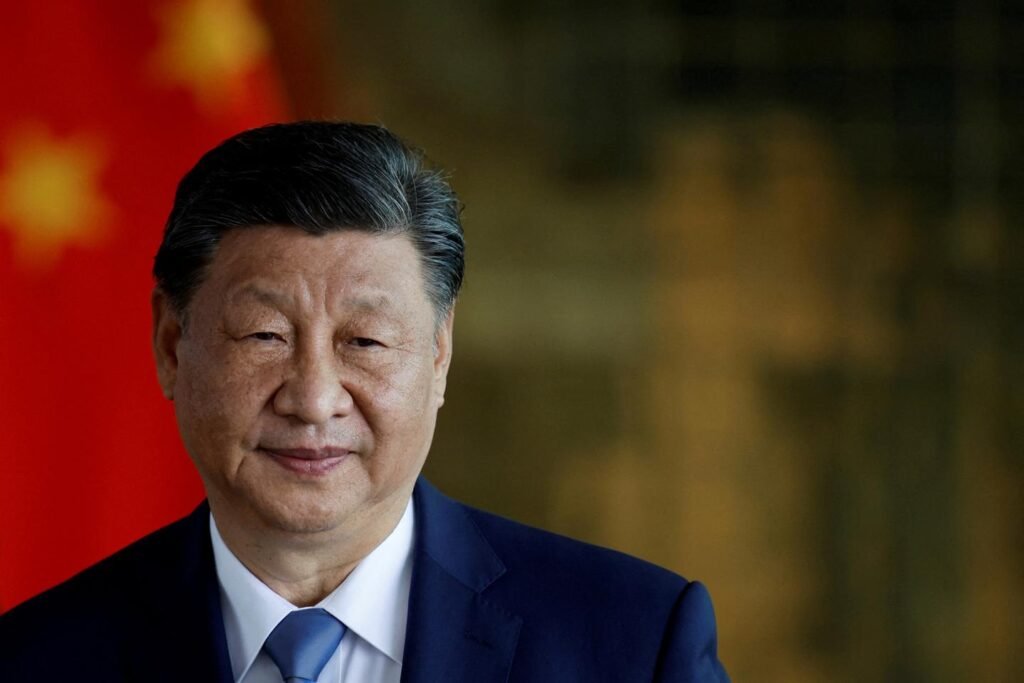

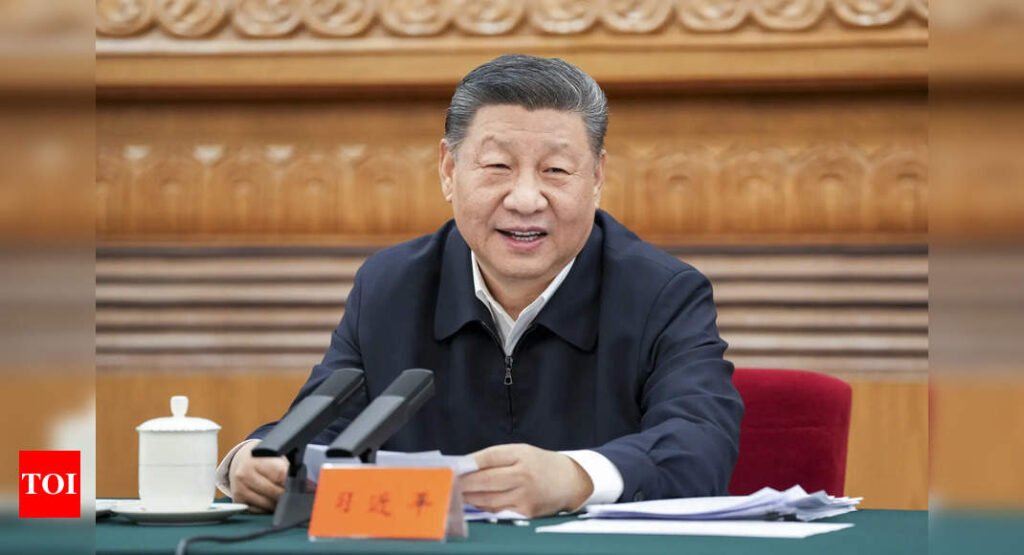

On the other hand, it should by now be obvious not just that Trump’s strategic agenda is more radical and far-reaching than in his first term, but also that his ferocious transactional instincts risk pulling his approach to China in directions that would be entirely welcomed by Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Indeed, as it’s viewed from Beijing, Trump’s second start in the White House already presents myriad unexpected opportunities for China to exploit.

Those who support a more competitive approach can still point to early wins. Trump has lambasted European allies but been much gentler in Asia. Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba enjoyed a successful trip to Washington in early February, and a visit by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi last week demonstrated an Indo-U.S. relationship in seemingly rude health. Trump’s team reaffirmed its support for the Australia-United Kingdom-United States pact (known as AUKUS) while U.S. warplanes conducted joint patrols above the South China Sea to support the Philippines. And by browbeating Panama, the United States persuaded it to abandon China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

More starkly, Trump’s approach to Ukraine—his demand that European nations provide security guarantees for any peace deal as well as Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s declaration that Washington is no longer “primarily focused” on Europe’s security—bears the hallmarks of an administration that is serious about prioritizing the Indo-Pacific over other parts of the world. “America, as the leader of the free world defending American interests, is going to need to make sure we’re focused properly on the Communist Chinese,” Hegseth said on Feb. 12 during a trip to Germany.

Yet this apparent drive to prioritize competition with China stands in sharp contrast to Trump’s wider geopolitical approach—much of which will likely be a cause for quiet contentment in Beijing. Some of this links to Trump’s rough-and-tumble treatment of allies as well as China’s long-term hope that the United States’ globe-spanning alliance system might crumble. Just as important is Trump’s new embrace of a raw form of great-power politics.

His inaugural address featured little criticism of China, barring two references citing Beijing as the justification for Trump’s plan to retake the Panama Canal. Its other themes, including his neo-imperial aspirations for Greenland, will be welcomed by China—given that they align with its ambitions to control Taiwan and signal the demise of U.S. support for a rules-based order that China has long sought to end.

Much the same is true of the way that Trump is pursuing a great-power deal in Ukraine by reportedly handing concessions to Russian President Vladimir Putin while sidelining Europe. All of this plays to Beijing’s geopolitical advantage, given its quasi-alliance with Moscow as well as its long-term aims of driving a split between Europe and the United States and undermining NATO so that it cannot get involved in Asia.

Elsewhere, Trump’s policies are creating openings for possible Chinese influence. His controversial plan to take control of Gaza has sown discord—not just between the United States and the wider Middle East, but also among Muslim-majority nations in Asia, notably including Indonesia and Malaysia. His effort to shutter the United States Agency for International Development, while not a critical injury to Washington’s ability to manage great-power competition, reinforces Beijing’s narrative about U.S. unreliability.

More institutional disruption is likely to follow in ways that will further benefit Beijing, from the hollowing out U.S. intelligence agencies to potential purges of military leaders.

China might not be able to capitalize on these opportunities, of course. But it will certainly attempt to do so. As Jin Yinan, a professor of military strategy at China’s National Defense University, once noted in a 2018 interview with the New Yorker, China will often claim in public that Trump’s policies do it harm, while actually quietly recognizing they provide opportunities. “As the U.S. retreats globally, China shows up,” he told the magazine.

None of this should be surprising. The weaknesses of Trump’s transactional approach to China were clear in his first term. At the time, he did push a new, hard-line approach to great-power competition with China and Russia. But he also struck erratic arrangements, from tariff deals to a plan to save ZTE, a Chinese telecommunications company. Xi’s part of his bargain with Trump—a commitment to a sharp increase in purchases of U.S. products—was never fulfilled or enforced. Trump’s deal-making instincts remain clear, from his invitation to Xi to attend his inauguration to his U-turn to preserve Chinese control of TikTok.

Beijing’s main hope will be to lure Trump into a big deal involving the status of Taiwan. Trump has shown little interest in supporting the island. He is known to be pessimistic about the United States’ ability to deter China’s long-term goal of unification. Trump’s policymaking style is notoriously unpredictable, and he has few fixed ideological convictions, but he remains a transactional leader. High-profile visits to Beijing, future summits with Xi, and the idea of striking a major deal will appeal to him. A new economic bargain must be conceivable—perhaps one in which China promises to invest in the United States in exchange for reductions in technology export controls.

For now, a grander bargain over Taiwan’s future may be a step too far, although some kind of fourth joint U.S.-China communiqué clarifying Washington’s position cannot be ruled out, adding to the existing three communiqués signed between 1972 and 1982 that act as a bedrock set of understandings for U.S.-China relations.

Either way, the very unpredictability of Trump’s approach—capable of shifting rapidly from aggressive tariff threats to warm personal diplomacy—makes it exceedingly hard for the hawks he appointed, or indeed U.S. allies, to judge what he might ultimately do.

Although they have welcomed Trump on the surface, those allies are clearly deeply nervous. During their meeting, Ishiba managed to get Trump to affirm the importance of stability across the Taiwan Strait—but it is hard to see how Japan or anyone else can rely on any statement not being reversed on a sudden presidential whim. Meanwhile, former Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong gave a striking speech on Feb. 8 in which he warned that “the U.S. is no longer prepared to underwrite the global order,” leaving countries like his own scrambling to cope and adapt.

Naturally, China’s leadership is not going to express in public that it senses a geopolitical opportunity. More likely, it will continue to suggest that the two superpowers “respect each other’s core interests and major concerns,” as Xi put it in a call with Trump in January. But just as Washington’s allies are worried in private about Trump’s willingness to upend core tenets of the existing international order, so too is Beijing is calculating that his second presidency will accelerate the very changes that China has long sought to achieve.