Archaeologists are revealing the secrets of a long-lost Stone Age civilization – believed to be the oldest in the world.

Ongoing investigations by Turkish, British and other archaeologists in southeast Turkey have unearthed 20 previously unknown sites.

Dating back around 11,500 years, the civilization appears to have been the first in the world to develop monumental architecture, sophisticated sculpture and advanced stone technology. The on-going discoveries are of huge international importance.

It also seems to have been the first human culture to develop large settlements – embryonic towns with populations of up to a thousand people.

So far around 30 settlements have been discovered – and archaeologists expect to find at least 30 more. Today, tourists can visit several of the sites currently being investigated – including Karahan Tepe and Göbekli Tepe and (betwen June and November) Sayburç, Çakmaktepe, Sefer Tepe and others – and can explore a remarkable museum, located in the city of Şanlıurfa, featuring sculptures and other spectacular finds from those and other sites of the world’s first embryonic civilization.

Mapped: Şanlıurfa in Turkey:

Although two of the sites were excavated as far back as the 1990s, nobody at that stage realised that they represented a large and previously unknown ancient civilization covering over 2000 square miles. It is more than twice as old as ancient Egypt or even Stonehenge and almost five times the age of classical Greece.

The civilization now gradually being revealed, appears to have been the first to create complex architecture – with rock-cut subterranean domed rooms (almost certainly equipped with corbelled ceilings) and large ritual halls, up to 20 metres wide, originally with vast timber, reed and mud rooves, supported by highly decorated pillars up to 5.5 metres tall (some weighing over 20 tonnes and probably symbolizing giant ancestors or deities).

The excavations are also revealing that the Stone Age people who constructed humanity’s earliest known sophisticated buildings some 115 centuries ago were also prolific monumental sculptors. Over the past two years, archaeologists excavating at several sites have unearthed giant sculptures – including a 2.45 metre tall statue of what was probably a revered or even defied ancestor.

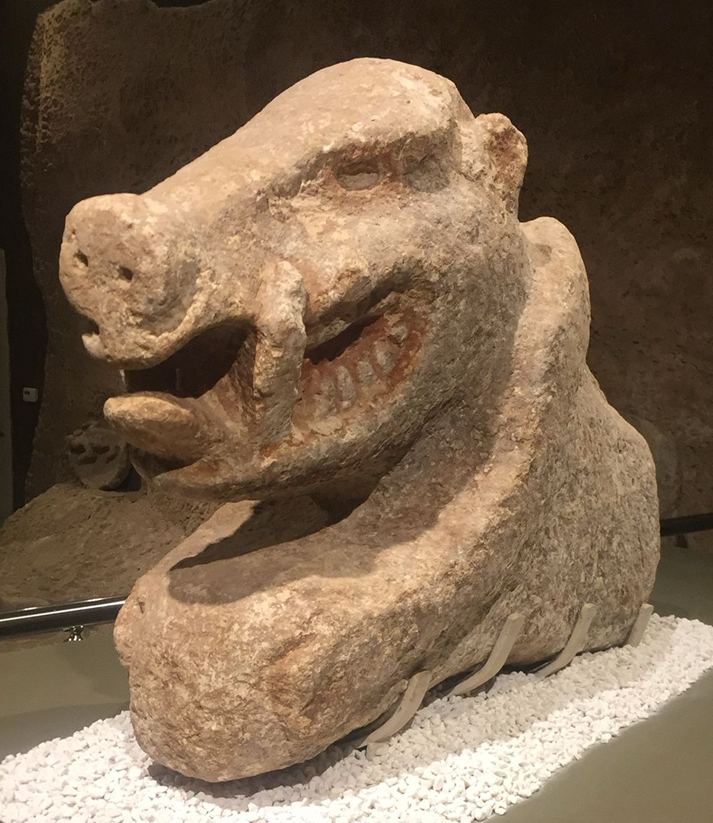

Other sculptures and carvings, unearthed by the archaeologists over recent years, have included images of leopards, crocodile-like creatures, snakes, giant cattle, wild boar, vultures, other birds, wild goats, frogs and scorpions.

It’s probably significant that most of the animals portrayed would have been perceived as physically very powerful and dangerous. Some images show humans transformed into or masquerading as such animals – and it is therefore conceivable that the sculptures were attempts to enable humans to spiritually harness animal powers (or to express people’s totemic beliefs that they were ultimately descended from such powerful creatures).

But many other sculptures portrayed human heads – and some rooms at some of the excavated settlements were filled with dozens of real human heads. That, in turn, suggests the practice of some sort of head or skull tradition – perhaps connected to ancestor cults (or, less likely, head-hunting activities).

The civilization, now known as the Taş Tepeler (literally ‘Stone Mounds’) Culture also appears to have had some sort of fertility-centred belief system. So far, at several sites, the archaeologists have discovered very large statues portraying men holding their penises. In one particularly spectacular example, a man is portrayed in semi-skeletal form – so it may be that the sexually explicit sculpture, located in an apparently ritual building, represented a key dead ancestor’s crucial role in promoting human fertility among his living descendants (or alternatively an extreme ritual fasting tradition).

A sexually explicit image of a woman has also been found – her legs apart, displaying deliberately elongated private parts.

Evidence from the sites currently being investigated, suggests that the 11,500-year-old culture was not only architecturally and artistically advanced, but was also socially highly complex and developed.

Indeed, some artefacts have what appear to be symbols on them – and some specialists are now assessing the possibility that the civilization developed a very early form of ideographic writing.

The information being obtained from the current excavations is likely to prove essential to understanding the origins of human civilization.

The southeast Turkish Stone Age culture, now being revealed to the world, is important for three key reasons.

- Firstly it’s the oldest really sophisticated socially complex human culture ever discovered.

- Secondly, it’s the earliest known example of monumental architecture and large settlements in humanity’s story.

- And thirdly, it represents the fragility of such cultures – because, despite lasting up to 1500 years, it collapsed and disappeared without trace, until its recent rediscovery.

As such, it’s a key example of precocious advanced, yet ‘dead-end’, cultures or proto-civilizations which came into existence thousands of years ago – and which were not then replicated in any way, in their respective areas, for several millennia.

In most cases, although people’s descendants continued to exist, their complex societies and cultures simply didn’t.

There are relatively few examples of early ‘dead end’ sophisticated cultures – and the remarkable long-lost Stone Age civilization in southeast Turkey is probably the most remarkable and certainly the oldest of them. But others flourished and then vanished throughout prehistory – 4400 years ago in North America and in East Africa and some 7000 years ago in Western Europe.

In the oldest example – the one currently being investigated by Turkish, British and other archaeologists – sophisticated monumental architecture did not re emerge anywhere in the world until 3500 years later (when sophisticated architecture and early urbanism began to re-appear – this time in southern Iraq.

Although the southeast Turkish Stone Age civilization did eventually collapse (around 10,000 years ago), it had flourished for some 1500 years.

It appears to have been a relatively stable culture for most of its existence – and its population seems to have lived in what may well have been a real-life Garden of Eden.

Food was plentiful – and recently discovered archaeological evidence suggests that they feasted on wild deer, boar, gazelle, horse, giant cattle, wild sheep, hare and goats.

What’s more, they lived in well-built houses in often planned and well-designed settlements – and existed in apparently peaceful well-organised societies.

Although, for most of the culture’s existence, they had no knowledge of metal or even pottery, they were able to make everything they needed from stone, bone, wood, animal skin, reeds and plants.

For them, stone was the steel, the plastic and the porcelain of their era. With it they made beautifully crafted bowls, plates, sculptures, tools, weapons and exquisite jewellery (sometimes made of jade!)

But their prehistoric Garden of Eden had emerged out of much more challenging times. For the roots of their culture lay in their ancestors’ ability to adapt to a 1200 year long period of climatic deterioration – a return to Ice Age conditions which had suddenly forced them to adapt and modernise.

The leading Turkish archaeologist involved in the excavations, Istanbul University’s Professor Necmi Karul says the discoveries are of “huge international importance”.

The ongoing investigations are harnessing expertise and recourses from 33 academic institutions in Turkey and around the world. As well as Turkish archaeologists, there are British, German and Japanese academics involved – and the Chinese will be helping as from this Summer.

British archaeologists are working on several aspects of the investigations – and the University of Liverpool’s Professor Douglas Baird, a leading Neolithic expert, is directing an excavation at a key Taş Tepeler site called Mendik Tepe.

The development of settled life in the area “saw the rapid development of monumental architecture representing the world’s earliest corporate institutions and large scale purpose-built ritual buildings as part of widespread networks of communities”, said Professor Baird.

Over the past 22 months, archaeologists excavating at one of the Taş Tepeler civilization’s largest sites, Göbeklitepe, discovered the world’s oldest known life-size animal sculpture (a huge stone boar), while at nearby Karahantepe, they unearthed one of the Stone Age world’s most spectacular ritual deposits, consisting of wolf jaws, leopard and vulture bones and fox claws (which had been attached to their skins), as well as animal figurines and 40 stone bowls and plates, decorated with animal images.

Excavations at more than a dozen key Taş Tepeler sites will restart in just a few weeks time – and further major discoveries are expected.