A series of recent social media posts from the Trump administration’s official government accounts have echoed terminology used by far-right extremists, experts said, adding that the posts offer no doubt that they are references to white supremacist rhetoric.

One of the posts, published by the White House X account Wednesday, shows two groups of sled dogs with Danish flags, one path headed toward a U.S. flag and the other path headed toward the flags of Russia and China. Above the photo, the text reads: “Which way, Greenland man?”

In August, the X account for the Department of Homeland Security used similar wording as a caption for a drawing of Uncle Sam with a recruitment call for Immigrations and Customs Enforcement: “Which way, American man?”

That phrase closely mirrors the title of the 1978 book “Which Way, Western Man,” which is an important text to white supremacist groups and remains in use by extremists online.

Robert Futrell, a professor at the University of Nevada Las Vegas who has studied far-right extremism for more than two decades, said that the phrasing in relation to the way many in the Trump administration have talked about immigration points to what he called “movement rhetoric.”

“I think connecting the phrasing of ‘Which way American man,’ especially paired with the ideas of cultural decline, the ideas of invasion, the idea of homeland, it’s connecting the phrasing to a white supremacist canon.”

Another image posted to the X, Facebook and Instagram accounts of Homeland Security includes a photo of a man on a horse silhouetted against snowy mountains as a B-2 stealth bomber flies overhead.

“WE’LL HAVE OUR HOME AGAIN,” text over the image reads. “JOIN.ICE.GOV”

Those words are well known in the far-right community as the title and lyrics of a song embraced by white nationalists.

Some on the far right have acknowledged those posts as being aligned with their views. Wendy Via, co-founder and CEO of the nonprofit Global Project Against Hate and Extremism, pointed NBC News to channels on the messaging app Telegram in which members of the Proud Boys circulated the posts.

“Message received,” read one message posted alongside the Homeland Security post on X.

A third post, published last week to X by the Labor Department, used the phrase, “One Homeland. One People. One Heritage,” which some critiqued as un-American. Many others online said it bore similarities to a Nazi propaganda slogan: “Ein volk, ein reich, ein führer,” which translates to “One people, one empire, one leader.” The post drew the ire of many union leaders, The Guardian reported.

The White House and Homeland Security did not immediately respond to requests for comment. A White House spokesperson told Politico in response to questions about the posts: “This line of attack is boring and tired. Get a grip.” A Homeland Security spokesperson told the publication: “Calling everything you dislike ‘Nazi propaganda’ is tiresome… DHS will continue to use all tools to communicate with the American people and keep them informed on our historic effort to Make America Safe Again.”

NBC News contacted six academics who have spent much of their careers studying extremism. All saw the posts as references to far-right ideology that is making its way into the mainstream and tied to the Trump administration’s immigration push, which has increasingly embraced terms like “invasion” to describe the entry of unauthorized immigrants to the U.S.

“These are no longer dog whistles,” Jon Lewis, a research fellow at the Program on Extremism at George Washington University, said. “They’re bullhorns.”

“It sends that emboldening message to neo-Nazis and white supremacists that the government is on your side,” Lewis added.

Lewis said each post “ends up being linked in countless conspiracy theory channels, countless extremist online spaces, and they view that as success.”

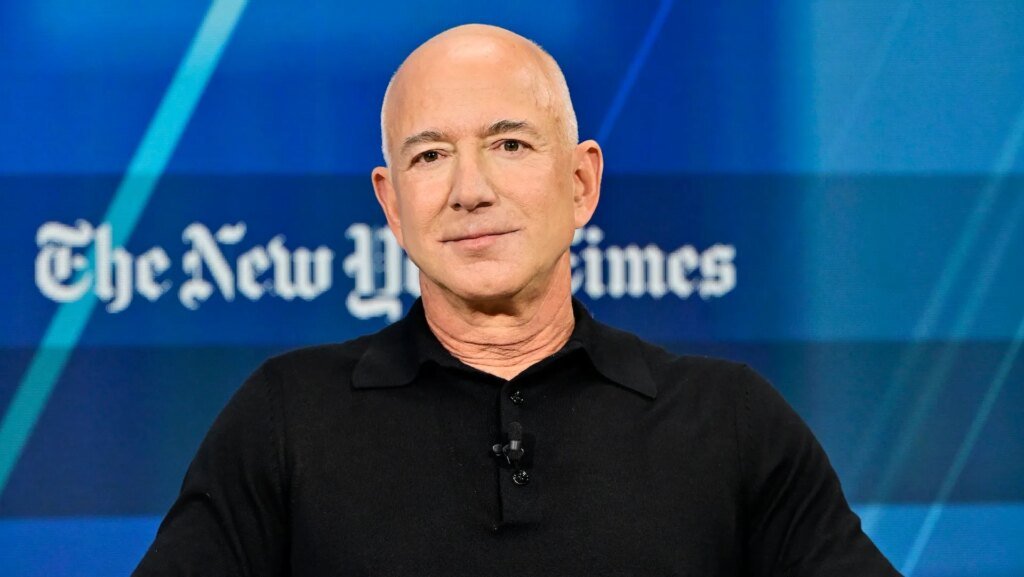

The posts, which account for only a small fraction of the government’s posts, come as some in Trump’s orbit have more openly embraced extremist rhetoric. Tech billionaire and X owner Elon Musk, a former Trump administration adviser who dined at Mar-a-Lago earlier this month, boosted a post that read in part: “If white men become a minority, we will be slaughtered. White solidarity is the only way to survive.”

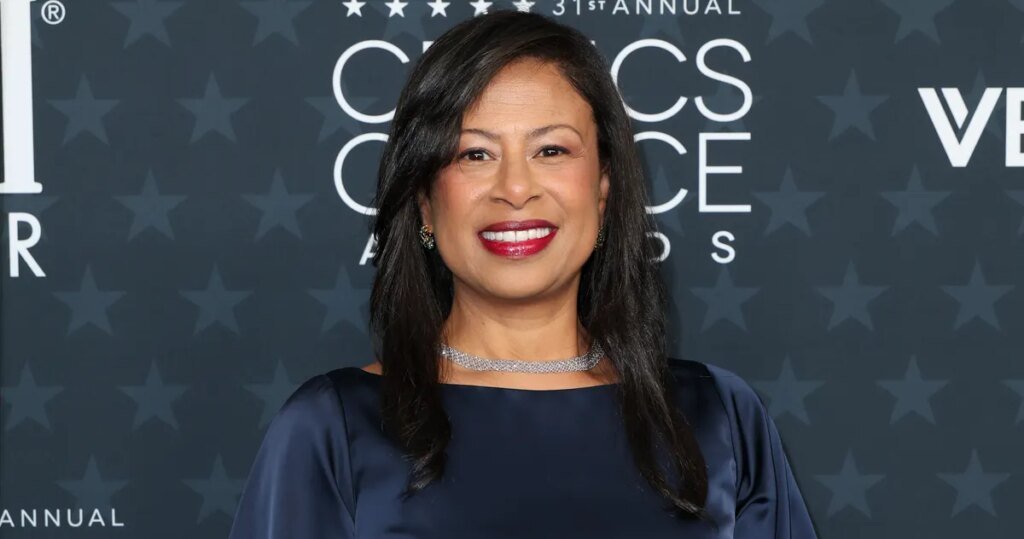

Jessie Daniels, a professor in the department of sociology at CUNY’s Hunter College who has studied far-right extremism and media for more than three decades, said there was “zero doubt” that these posts were meant to echo white supremacist rhetoric.

“They’re very clearly intending to signal their allegiance to a rather overt white supremacist ideology,” she said.

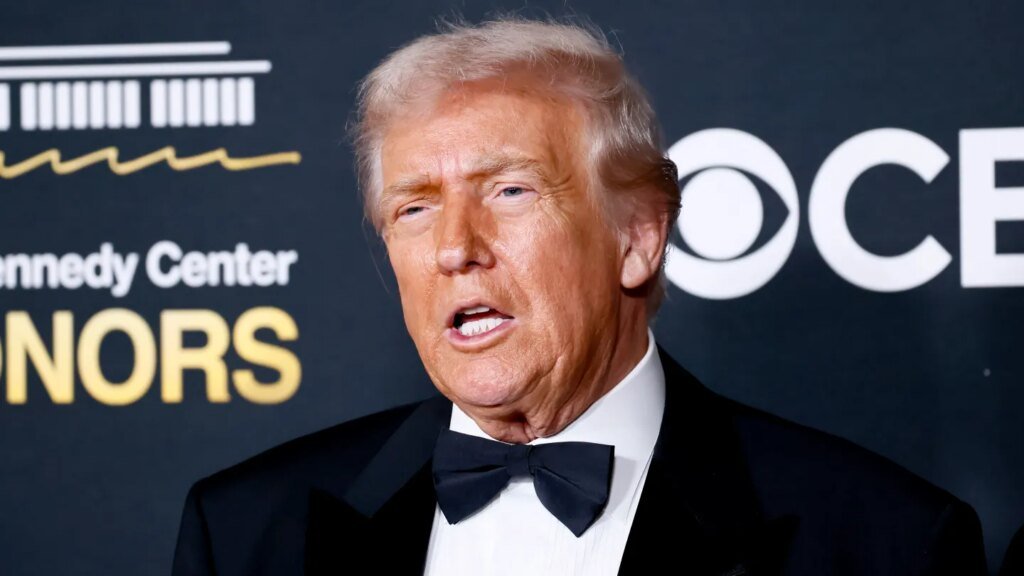

Throughout his political rise, Trump and members of his family have been scrutinized for posting messages that nodded to extremism. In 2016, Donald Trump Jr. and former Trump adviser Roger Stone posted images that included an internet meme called “Pepe the Frog,” which had become popular with the alt-right. Trump himself has at times elevated subtle and unambiguous extremist content, from QAnon conspiracy theories to a 2020 video on Twitter of a man wearing his campaign gear and shouting “white power.” Trump later removed the post and the White House said at the time that the president had not heard what the man was shouting.

This content presence has more notably extended to official government accounts in Trump’s second term, complete with memes, AI-generated imagery and unapologetically MAGA messaging. Some of that imagery is more subtle than others, such as in July when Homeland Security posted to social media, “A Heritage to be proud of, a Homeland worth Defending” with a photo of John Gast’s “American Progress,” an 1872 painting that portrays Miss Columbia (representing America) and white settlers advancing westward as Native Americans appear to flee.

Whether that image was meant to be an expression of patriotism or a wink at white supremacy was the subject of some debate.

More recent posts from the administration with content that can be read as extremist have “gone from episodic to more consistent, and it’s gone from more gray area to more clear cut,” said Peter Simi, a professor of sociology at Chapman University who has studied extremist groups since the mid-1990s.

Simi said that the posts, even as clear as they are to people versed in extremist rhetoric, offer some cover for the administration to say they are patriotic. He noted the chance of the phrase “Which way, Western man?” to “Which way, American man?”

“And so even in a pretty overt kind of post, there is an effort to create plausible deniability, and that is a very common strategy in the kind of creation of propaganda on the far right,” he said.

Lewis noted that the format of these posts, many of which embrace memes and meme-like formats, have been used for years successfully by hate groups to push their ideas to the public.

“But what we’ve seen in recent years is the popularization of this meme culture, of this coded language, these sort of ironic, half-joking, wink-and-nod references that have far more sinister, insidious meanings,” Lewis said.

Cynthia Miller-Idriss, a professor and director of the Polarization and Extremism Research & Innovation Lab (PERIL) at American University, said in an email that it’s not necessary for people to know the origins of the posts for them to be effective messages.

“Propaganda works well when it gets people to transfer warm feelings from prior experiences or histories or movements to something new,” she wrote. “It’s an effective persuasive tactic and very intentional in terms of trying to get Americans to fall in line behind ICE, behind mass deportations, and to come along and onboard this patriotic journey to set things right again.”

So far, outcry is limited. While many on social media have pointed out the connections, few if any prominent Democrats have weighed in on them. Some who have been supportive of Trump appear unconcerned.

Sam Markstein, communications director at the Republican Jewish Coalition, said in an email asking about the social media posts: “Republicans won’t be lectured on so-called ‘extremism’ from a Democratic Party that cozies up to jihadi sympathizers, let tens of millions of illegal aliens pour into the country, believes men belong in women’s bathrooms and sports leagues, and thinks that what’s happening on the streets of Tehran, as courageous civilians protest a barbarous regime, is somehow equivalent to ICE enforcing immigration law in Minnesota.”

Some of the experts that spoke to NBC News stressed that the posts could resonate well beyond social media and that the phrases and visuals used by the Trump administration could serve multiple purposes: benign messaging to the public at large, signals of approval to extremists and fodder for social media attention.

“In the current technological moment, it’s less about ideological precision, more about rhetorical and political impact of messaging,” Heather Woods, an associate professor at Kansas State University who studies the social impacts of technology, said in an email.

“The benefit for the administration is that these images — often shared directly on social media or tailor-made to go viral on social after the fact — generate a great deal of interest and attention,” Woods added.

“The fact that we are debating whether or not they are specifically aligned with a particular ideology is, in fact, amplifying their messaging,” she continued.

Futrell, the University of Nevada professor, also stressed that overt references to extremist texts were only part of the concern and that other terms and ideas that were once confined to the fringes had made their way to the highest echelons of government — something that has not gone unnoticed in far-right circles.

“So you’ve got terms like invasion, re-migration, cultural decline, they look like ordinary politics to casual readers, but they function as really recognizable signals inside far-right networks,” Futrell said.