Sundaram and Amin are in pursuit of the Holy Grail—printing an actual organ like a heart, liver, or kidney. World over, researchers are trying to engineer human cells and tissues for this purpose. It holds the promise of revolutionising medicine. Donor lists would be redundant. Organ rejection would be a thing of the past. Doctors would simply take the patient’s cells and print a brand-new organ.

It’s not yet a reality, but it’s no longer in the realm of sci-fi. So far, the closest scientists have come is 3D printing human-like heart tissue from stem cells.

But it is not yet ready for human tissue replacement.

“It’s an inspiring space, but the 3D printing technology ecosystem has not yet matured, in terms of its applications,” said Taslimarif Saiyed, director at Centre for Cellular and Molecular Platforms (C-CAMP), which supports new profound science-based innovations in healthcare. Printing human organs throws up a host of challenges from ethical issues and data privacy to high costs and the complex microenvironment of living tissues.

“Once the technology improves, and regulatory barriers are eased for its use for humans, the field will explode.”

But it has the potential to revolutionise the field of regenerative medicine and clinical rendition and to lead to the development of new rehabilitation for various diseases in the days to come.

And India is part of this race. In February 2022, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) unveiled the National Strategy for Additive Manufacturing Policy to increase India’s share in global 3D printing to 5 per cent within the next three years. Since then, the programme has seen 42 startups enter the field.

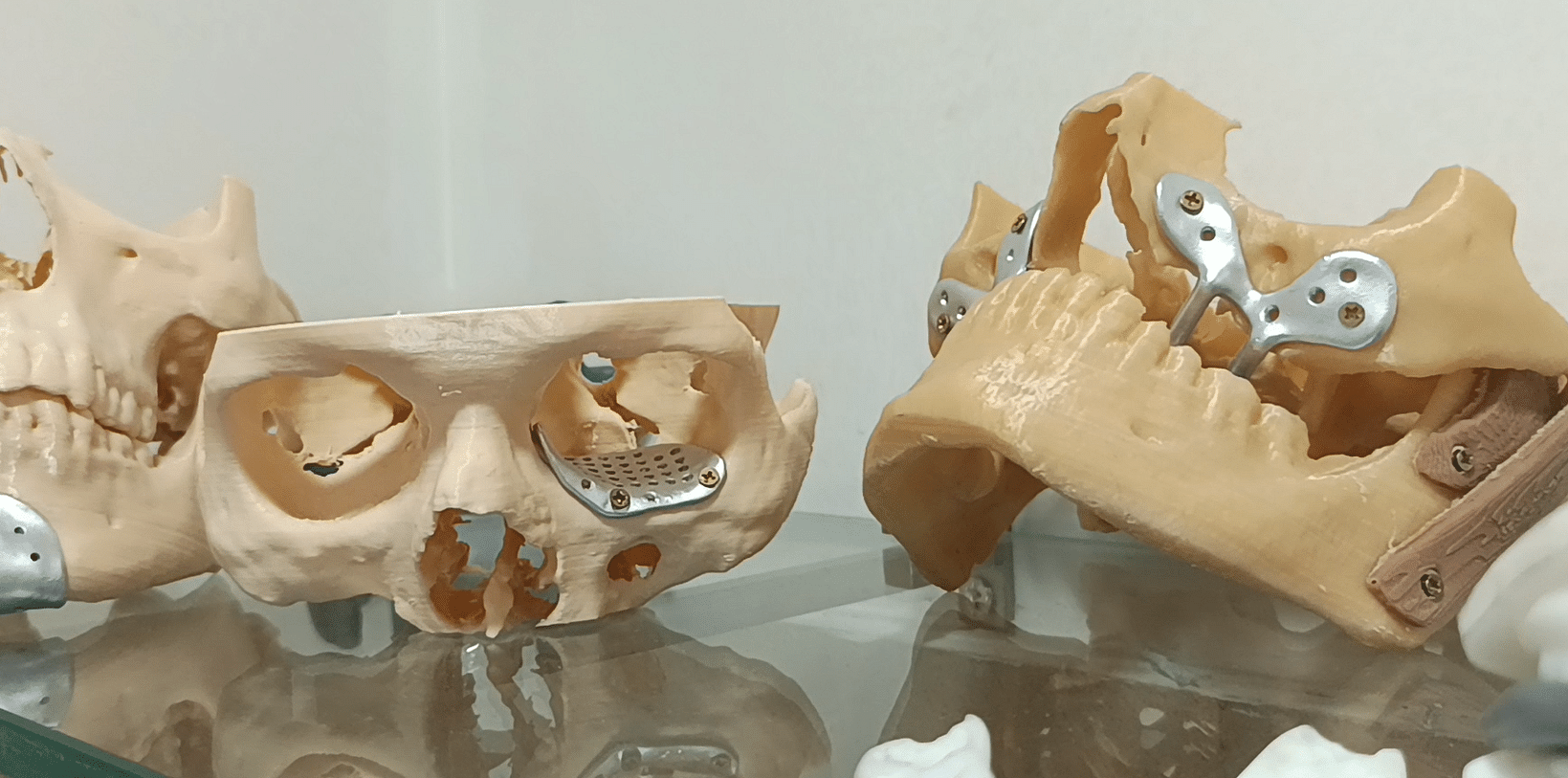

Already, startups and hospitals are using 3D printing technology to improve drug development, and patient care, and plan surgeries. They are relying on 3D printing or additive manufacturing to reconstruct models of bones and organs for complex surgeries to remove malignant tumours and reconstruct shattered knees.

“Once the technology improves, and regulatory barriers are eased for its use for humans, the field will explode. Then you will not have issues like people waiting like in the case of corneal blindness for a donor,” said Saiyed.

Printing liver cells

Outsiders are not allowed into the ‘clean room’ at Avay Biosciences’ headquarters in Jayanagar, Bengaluru. This is where the liver cells—sourced from cell banks in India—are stored in liquid nitrogen.

Usually, researchers source animal cells, put them in a petri dish, and study them under a microscope, to understand how tissue works. However, this traditional 2D cell culture offers very little information. Effective communication in this case among cells is limited to just two dimensions, said Amin, an electronics and communications engineer and director at Avay Biosciences. “In a 3D printed model, a cell in an extra dimension provides space for better communication among different cell types in a single tissue.”

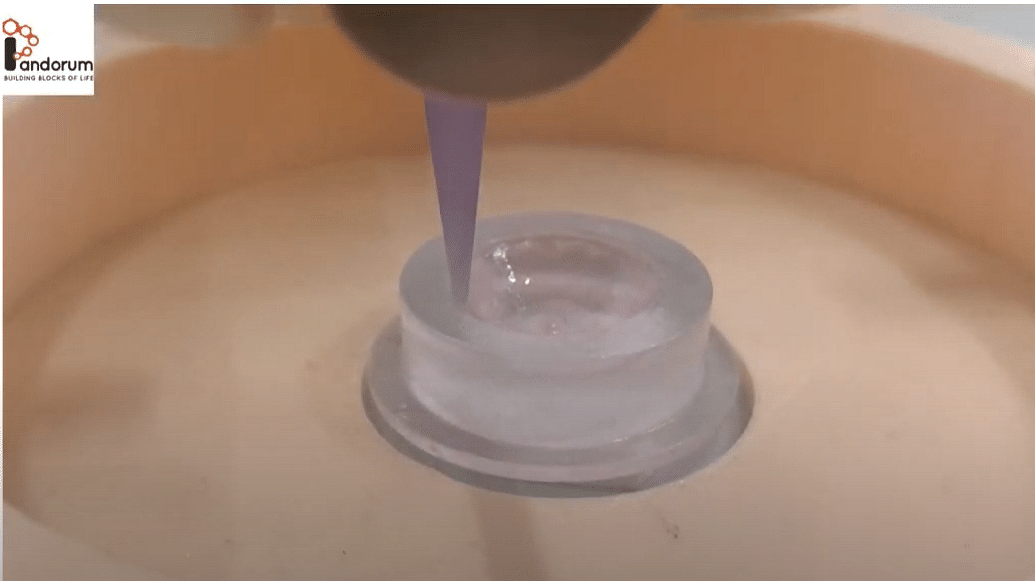

But before they start printing, biomedical engineer Priyanka Paul carefully mixes the liver cells to prepare ‘bioink’. First, the team sources the biomaterial from a private manufacturer. “Then we design the main concentration of biomaterial to print a 3D construct. When we mix our biomaterial and the cells, we get 3D bioink,” said Paul.

All this has to be done in a sterile environment. Once the bioink is ready, it is transferred with the help of a loading syringe.

“It’s a tricky process. There should not be any trace of even air bubbles which might damage the final product,” said Paul. The next step is to load it to the 3D printer. Before Paul presses the start button, she makes sure that the nozzle of the printer and the filament on which the print is to be made is aligned, the process of calibrating the printer.

The technology of 3D printing is not just limited to assisting drug development, but can also cure corneal blindness.

Just like how a singer would adjust his microphone to make sure their voice is thrown directly to the microphone, calibration ensures the printing nozzle is in place so that the ink is put correctly in the area to be printed.

The motion and the design of the nozzle depend upon the instruction given to the software using a technique known as slicing. Think of Google Maps. What slicing does to 3D printing is what Google Maps offers to someone who wants to go to a particular place. Slicing gives the printing nozzle directions on how it should move layer by layer, periodically.

Avay Biosciences wants to test the efficiency of various drugs used to treat liver failures. Acetaminophen, for one, is a widely used drug for mild liver diseases like non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Although the drug is extensively used, there are concerns regarding its effect on the patients.

The technology of 3D printing is not just limited to assisting drug development, but can also cure corneal blindness.

Also read: Search for an Indian Carl Sagan is on. Science influencers are being trained in labs and likes

Curing corneal blindness

One good thing about 3D printing cornea is that “we will never run out of bio-ink,”

On 14 January, Arun Chandru, founder of Pandorum Technologies received a message that a fire broke out at the Bangalore Bioinnovation Centre. It’s where Pandorum, which wants to print 3D corneas, has its research and development facility.

“No people were hurt, or data got lost but we lost a 3D printer designed to print cornea,” said Chandru. But it’s full steam ahead at the startup’s Ghaziabad setup where a team of researchers and doctors are printing corneas and testing them on rabbits at the Dabur Research Foundation.

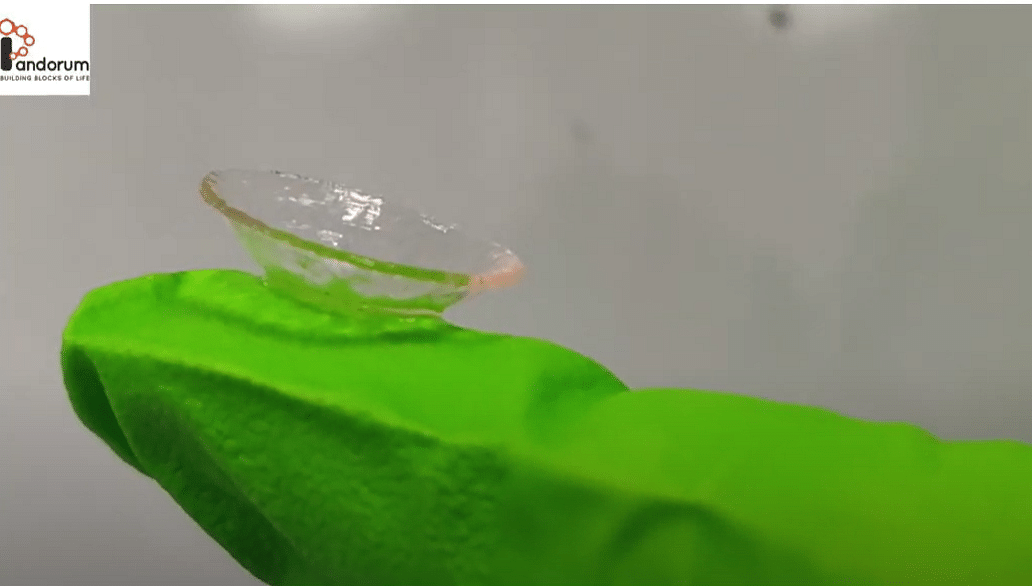

Chandru, who comes from an aerospace background, hopes to solve corneal blindness in India by working along with biomedical researchers and doctors. Pandorum’s 3D-printed cornea and its application are under consideration by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the US.

“This level of technology is far ahead of a regular startup,” said Chandru. Hospitals and research institutes like LV Prasad Eye Hospital and the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology among others have developed 3D-printed corneas as well.

In India, corneal blindness is considered a common cause of blindness after 50 years of age. The only solution is a corneal transplant. But there is a massive mismatch of demand and supply, said Parinita Agarwal, a senior research scientist at Pandorum Technologies.

The usual transplant is a daunting task where the doctor has to stitch the corneal transplant onto the patient’s eye.

Chandru’s team successfully tested the 3D-printed cornea made with the biopolymer Hyaluronic Acid and Gelatin on rabbits. It acquired the qualities of a regular cornea after the procedure. The printed cornea gets attached to the eye without a suture, bypassing another challenge in corneal transplant.

The startup uses BioX extrusion-based printers and Digital Light Processing technology to print the cornea. They have yet to test the technology on humans and are waiting for phase 2 and 3 trials to be finished.

One good thing about 3D printing cornea is that “we will never run out of bio-ink,” said Agarwal.

Both liver cell printing and corneal prints have not touched patient’s lives. But another aspect of this technology—non-bio 3D printing—is already being adopted by surgeons across India to perform complicated surgeries.

Surgery planning: doing it before doing it

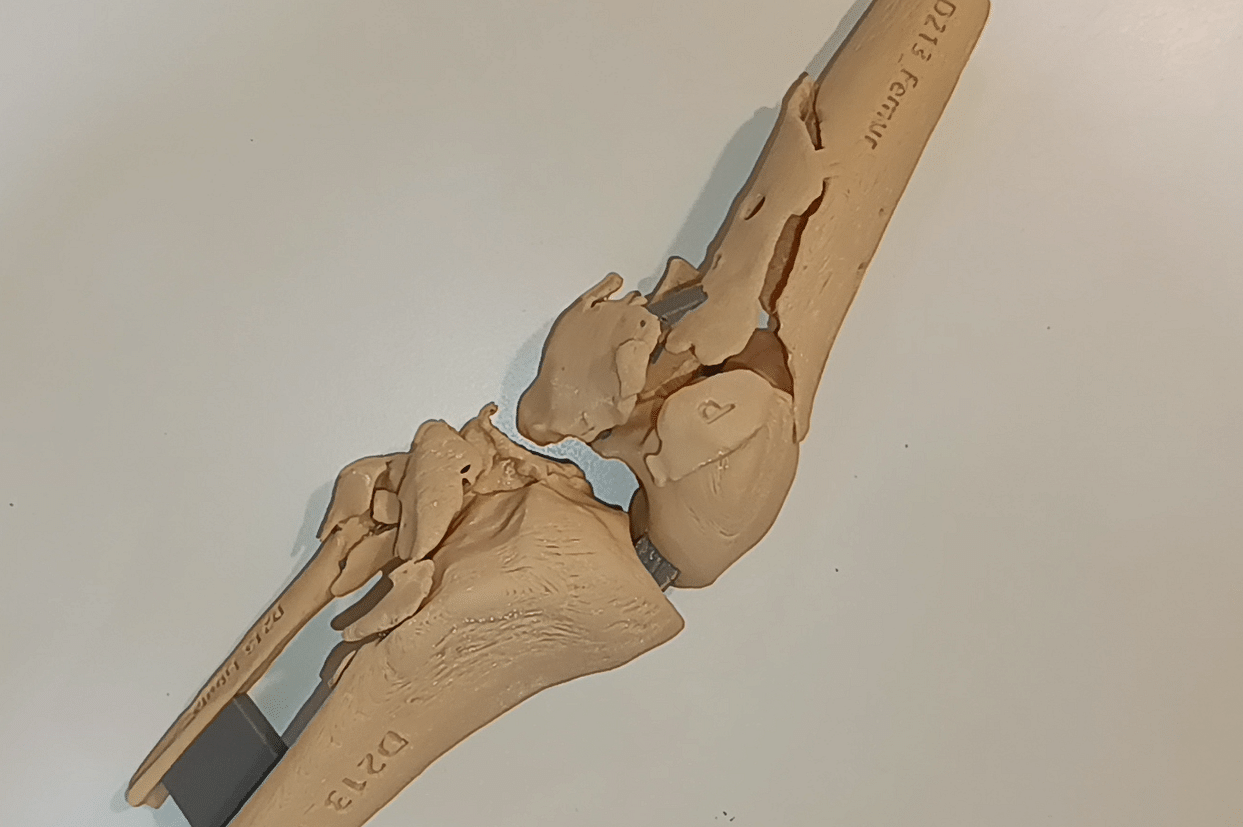

Flesh ripped off, bones severed, and parts of it thrown out, a 21-year-old engineer from Raichur survived a road accident in November 2024. But her knee was shattered. Her brother had one request to Dr Suraj Hindiskere at Sparsh Hospital: She should be able to move and bend it with ease.

“We could have easily fused the knee. A quick option, but the problem here is she will never be able to fold it,” said Hindiskere. But 3D printing of bones has given doctors an edge.

One of the advantages of patient-specific 3D bone is that the printed piece size is similar to the patient’s original bone. There are no surprises at the operation table. In Hindiskere’s words, 3D printing allows a surgeon “to do the surgery before the surgery.”

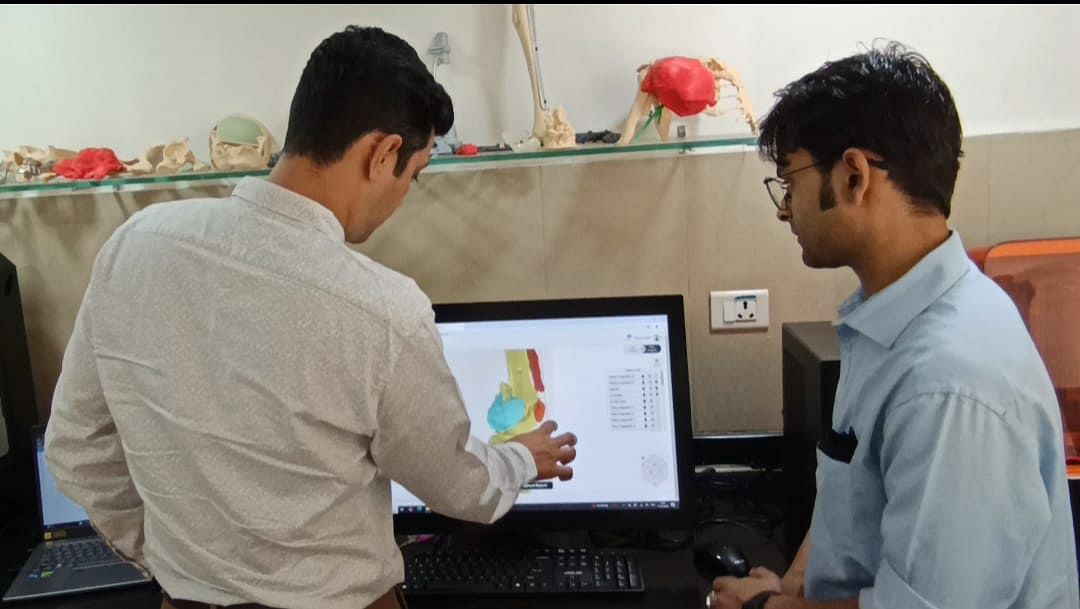

To print the 3D bone model, Hindiskere sought the help of Kumar Sukrit, the medical design engineer at Sparsh Hospital.

“In order to have a proper visualisation assessment of the severity of the case, the doctor wanted an anatomic model of the knee bone,” said Sukrit.

The team identified how much muscle was left behind, how much bone was lost, and the shape of the injured bone orientation.

“We also identified how much volume of bones we needed to reconstruct and what route we needed to take to do the surgery and enter,” said Hindiskere. Although most of the identifying process is automated, an engineer needs to sit and finetune the properties in software for accuracy.

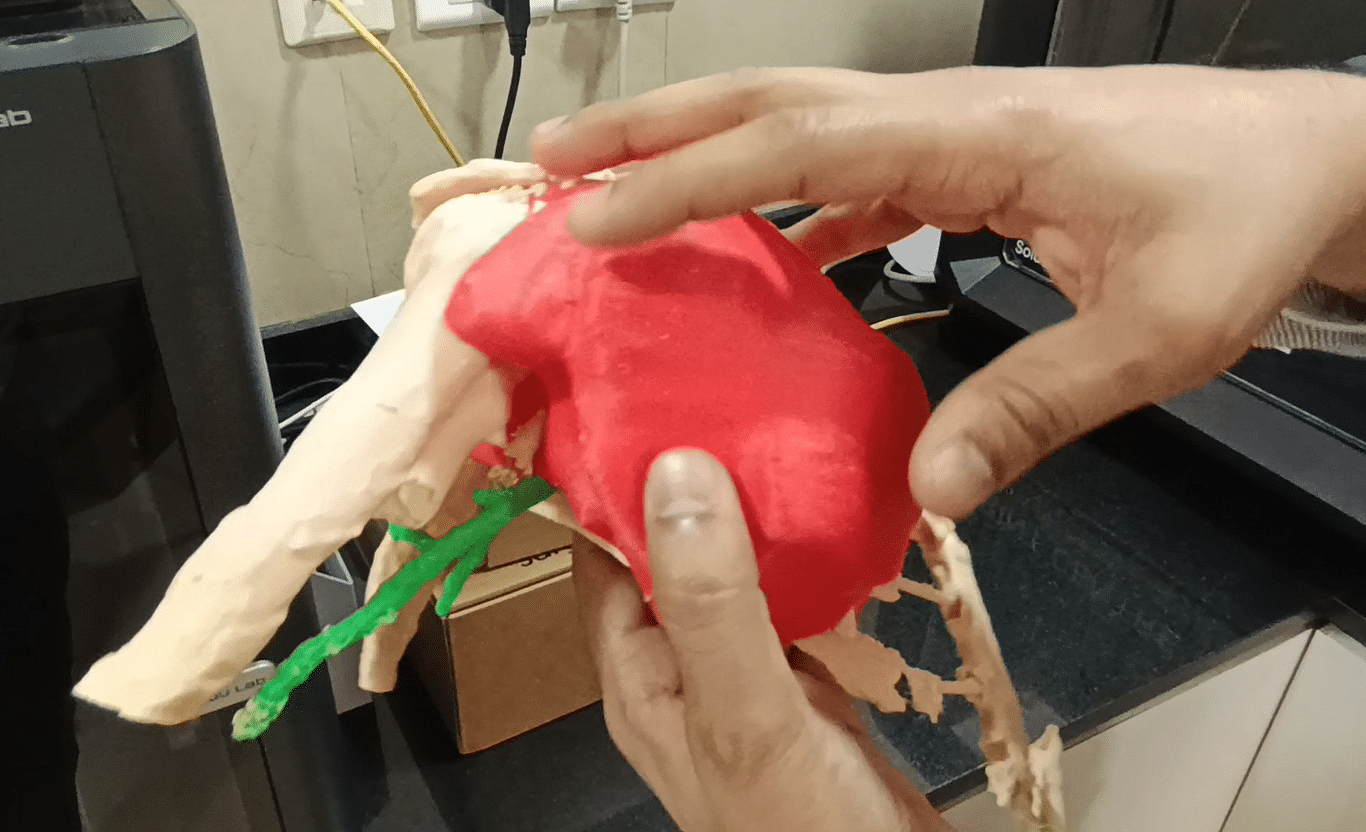

Once the scanned image identifies bones, muscles, and necessary details for the surgery, the design is sent to the printer loaded with the material. In this case, it is flesh-friendly plastic.

The process starts as the nozzle slowly prints layer by layer according to the design of the bone model. After finishing each layer, the nozzle repeats the same motion on top of the existing layer. This way, the print comes out in a three-dimensional form.

Photo: Ananthapathmanabhan, ThePrint

“There is a lot of surgeon-engineer interaction that I feel is the key to the successful 3D model,” said Hindiskere. Once the bones are printed, the model is sent for deep cleaning through different sterilisation methods. So, the doctors can touch the model with their operating gloves while performing the surgery.

As an ortho-oncologist, Hindiskere has even used a 3D-printed model of the chest wall to understand the size of a bone tumour, which helped him remove cancer with better precision. The procedure is the same here: the patient’s scan is taken and fed through a computer to understand the nature of the tumour and print the model.

In some cases, the 3D printer can also be used to print stencil-like structures called gigs and guides, to make the exact cut at the cancer area inside the body as the surgery is performed. Specific implants can be printed using the same procedure. Whether it’s gigs or the implants, a particular print will only fit for a single patient for whom the design is made, according to Hindiskere.

Whose bone is it?

There should be more focus on giving support to MedTech entrepreneurs in translating it from the research stage to the market stage

Machines printing patient-specific bones have added more contours to the privacy debate.

“Digital watermarks placed within 3D prints pose a challenge to the privacy of individuals,” said the authors in the 2020 study which calls for a regulatory body to provide guidance and support.

In India, although the Medical Devices Rules 2017 under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act (DCA) don’t specifically mention 3D-printed medical devices, it can be applicable using interpretation, said Shivangi Rai, deputy coordinator at Centre for Health Equity, Law and Policy (C-HELP). But then in computer-aided design files such as digital patient records, one has to get help through the Digital Data Protection Act (DDPA) 2023, rules of which are yet to be implemented.

Until these rules are in action, a consumer has to rely on Sensitive Data Protection or Information Rules 2011, which have similar provisions such as protecting present and past health records, sexual biometric data, and sexual orientation. Rai argued that there is no need for a separate section on 3D-printed devices.

However, 3D printing has increased the urgency of a robust data protection framework for patients. Another raging debate is the ethical implications of printing human organs.

“First, there should be more focus on giving support to MedTech entrepreneurs in translating it from the research stage to the market stage,” said Amin.

As policymakers untangle the ethical ramifications, doctors and researchers are celebrating small victories. The 21-year-old woman whose knee had to be reconstructed can now walk and even bend it to an extent.

“I tell everyone—this technology is changing lives,” said her brother.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)