Muslims around the world observe Ramadan fasting as an annual practice of worship where healthy and able individuals refrain from eating and drinking from sunrise to sunset.

Ramadan is about prayer, reflection, and charity, and offers an opportunity to enhance physical and mental health.

Self-disciplined acts favouring the reduction of unhealthy behaviours such as smoking are vital.

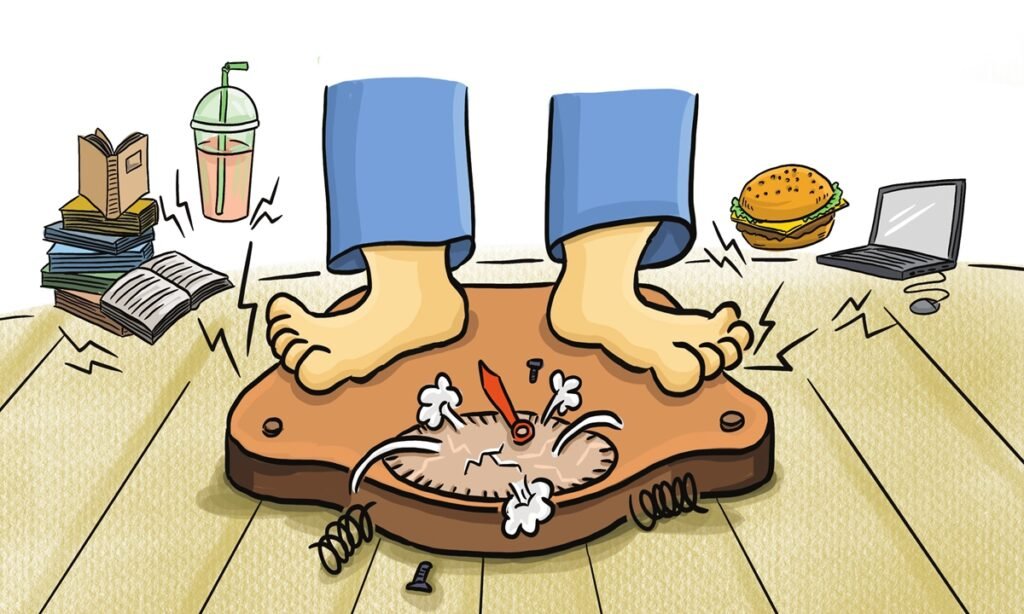

Although health benefits of fasting have been reported, lifestyles tend to change drastically during the Holy Month.

This is often associated with decreased physical activity, increased sedentary behaviour, and reduced sleep, all of which constitute important risks for health.

These changes are influenced by cultural practices emphasising family time and meal gatherings from the cannon firing at the break of fast (“Iftar”) to the early calls of Suhoor.

The country comes to life post-Iftar, and most activities and shopping centres operate until the late hours to provide opportunities to enjoy the Holy Month after the Taraweeh (evening) prayers.

Being moderately active in Ramadan has been shown to lead to better coping with fasting, better hydration status, and helping to maintain physical fitness and mental well-being.

Some definitions and distinctions are required.

Physical activity is considered any bodily movement that increases our energy expenditure above the resting level and includes daily tasks such as carrying grocery bags, doing the dishes, or house chores.

Exercise on the other hand is a structured form of physical activity with a goal to improve health, fitness, or performance.

Exercises include yoga or aerobics, jogging, cycling, and rowing.

Finally, sport is a physical activity that includes aspects of competition and is governed by a specific set of rules and regulations, such as football or tennis.

While these terms are often used interchangeably in the context of health, the specific distinctions need to be acknowledged.

For a sedentary person who is finding difficulties committing to an exercise programme, focusing on reducing sedentary time and making more physically active choices can have significant positive impacts on health and motivation.

As a long-term result, the more active a person is, the better chances they have of tolerating higher doses of specific exercises and/or feeling joy or pleasure in physical engagement.

Physical inactivity is the fourth leading cause of mortality worldwide.

Sedentary behaviour is further associated with higher risk of all-cause mortality and chronic diseases.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that adults engage in at least 150-300 minutes per week of moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA) and perform muscle-strengthening exercises at least two times per week.

Physical activity recommendations for children and adolescents require them to engage in at least 60 minutes of daily MVPA for health benefits.

All individuals are advised to reduce their sedentary time.

It is nevertheless important to note that sedentary time and physical activity can act as independent components, whereby benefits from physical activity can be moderated by the time we spend sitting.

Research studies have demonstrated that even among those who meet the WHO physical activity guidelines, extended periods of uninterrupted sitting can still pose health risks.

For example, a person that engages in 150 minutes of physical activity per week can still be at an increased risk after sitting eight hours at work.

Those who lead sedentary lifestyles need to pay special attention to the independent influence of each component on their health.

Strategies to reduce sedentary time include breaking up sitting time regularly with short bouts of movements whether in the workplace or at home in front of the TV.

Other strategies include investing in a standing desk for work or substituting sitting with light-intensity or relaxing activities.

When it comes to Ramadan, the Qatar National Physical Activity Guidelines also contain recommendations specific to adults fasting during the Holy Month.

In sum, light-to-moderate intensity activities are generally favoured for fasting individuals, and correspond to activities that are subjectively perceived as “fairly light or easy” to “somewhat hard”.

For healthy adults, the best time to programme a structured physical activity session is 2-3 hours after Iftar.

This window offers an optimal time for proper hydration and avoiding any potentially negative effects of sustained effort.

Sessions performed before sunset (Iftar) should ideally not exceed 60 minutes and aim to end just before Iftar to allow ingestion of food and fluids within the ideal recovery period.

Accumulating shorter bouts of activities at any time of the day is also a great alternative to a single session, offering similar health benefits.

Targeted activities usually involve most of the body parts (large muscle groups) like walking, jogging, cycling or swimming.

For non-experienced exercisers, sessions should start gradually and also include warm-up and cool-down phases especially if the activity includes high intensities or loads.

As a general rule, any physical activity should be immediately terminated in cases where the fasting person feels dizzy, nauseous, or uncomfortable.

For people living with certain chronic conditions like diabetes or hypertension but nevertheless fasting, it is important to schedule a consultation with a physician before engaging in structured physical activity.

For many people, fasting exacerbates disengagement from activities that require physical effort.

Recommendations concerning physical activities required for health remain safe and important to follow during Ramadan.

To overcome feelings of fatigue or lack of motivation, it is advisable to focus first on making more active choices throughout the day and try to be less sedentary at home.

Ultimately, any minute of being active is better than none for your health, particularly during Ramadan.

Dr Lina Majed is an assistant professor at Hamad Bin Khalifa University (HBKU)’s College of Health and Life Sciences (CHLS).