In yet another sign of xenotransplantation creeping toward reality, a medical team at NYU Langone Health announced Tuesday that, for the third time, a kidney from a genetically modified pig had been transplanted into a living patient.

Surgeons performed the procedure over seven hours on November 25. The organ recipient, a 53-year-old woman named Towana Looney, is a resident of Alabama who has been on a waiting list for a kidney since 2017. In the late 1990s, Looney had donated a kidney to her mother. Years later, her remaining kidney began to fail after suffering damage from high blood pressure caused by a complication from pregnancy. High levels of antibodies in her blood made finding a matched organ donor highly unlikely.

Following the surgery, Looney has not had to be on dialysis for the first time in more than eight years. She was discharged from the hospital on December 6, equipped with wearable trackers that beam heart rate, blood pressure, and other health data back to her medical team. She is returning to the hospital daily for in-person evaluation, and she is expected to return home in three months.

“I am overjoyed. I’m blessed to have received this gift, a second chance at life,” Looney said during a news conference at the New York City hospital on Tuesday morning. “I’m full of energy, got an appetite I’ve never had in eight years. It’s like I can feel the blood pumping through my veins. I can put my hand on this kidney and feel it buzzing, it’s so strong.”

This is the third time doctors have performed a kidney transplant with an organ from a genetically modified pig. In April, the same team at NYU Langone treated a 54-year-old New Jersey woman named Lisa Pisano suffering from both kidney and heart failure, outfitting her with a pig kidney just days after implanting a mechanical heart pump. But inadequate blood flow soon damaged the kidney, and surgeons were forced to remove it six weeks later. Pisano was later transitioned to hospice care and died in July.

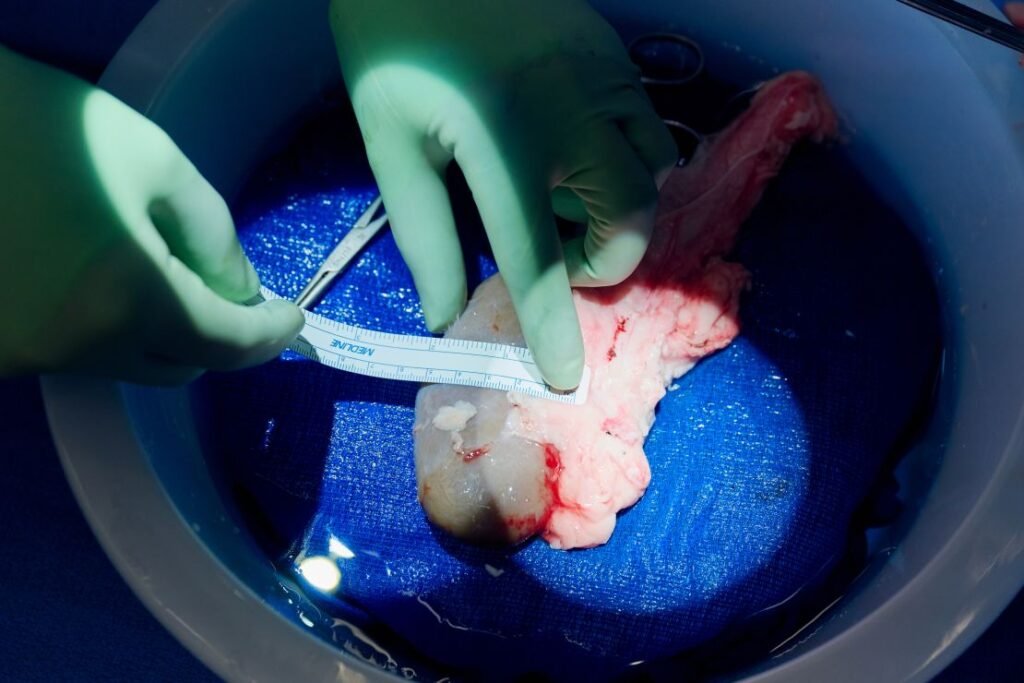

In both of the NYU transplants, the kidneys came from Revivicor, a biotechnology company spun off from the U.K. firm that produced Dolly the sheep, the first cloned animal. The company was later acquired by United Therapeutics. In Pisano’s case, the kidney originated in an animal that had been engineered to disrupt only a single gene — for a cell-surface sugar known as alpha-gal, which can trigger organ rejection by the human immune system. The kidney that Looney received was from a pig with 10 different alterations to its DNA, including the removal of two additional genes for molecules that trip the human immune system and a porcine growth hormone receptor.

In March, a medical team at Massachusetts General Hospital performed the historic first procedure with an engineered porcine kidney produced by eGenesis. Based in Cambridge, Mass., eGenesis has used CRISPR technology spun out of George Church’s Harvard lab to create a flock of Yucatan minipigs that carry 69 DNA edits. Similar to Revivicor’s animals, these alterations include knocking out genes for immune system-triggering molecules and adding ones to make the organs more compatible with the human circulatory system. Unique to eGenesis are dozens of instances of snipping out latent viral DNA woven into the pig genome — edits that eradicate the risk of any pig viruses accidentally hopping into humans.

The patient who received that organ, a 62-year-old man named Richard Slayman, was well enough to be discharged home two weeks after his surgery. But two months later, in May, he passed away due to an “unexpected cardiac event,” that his doctors said was unrelated to the transplant.

Although xenotransplantation research has undergone a renaissance in recent years, the procedures remain experimental and only available to patients too sick to be eligible to receive a human organ. The three transplants of kidneys from genetically modified pigs were approved under the Food and Drug Administration’s compassionate use program for patients at risk of dying without treatment.

Looney presents a somewhat unique case that her doctors hope will lead to better outcomes for her and more insights for the field of xenotransplantation. Although her high level of antibodies made the chance of finding a suitable human donor nearly impossible, she wasn’t on death’s door.

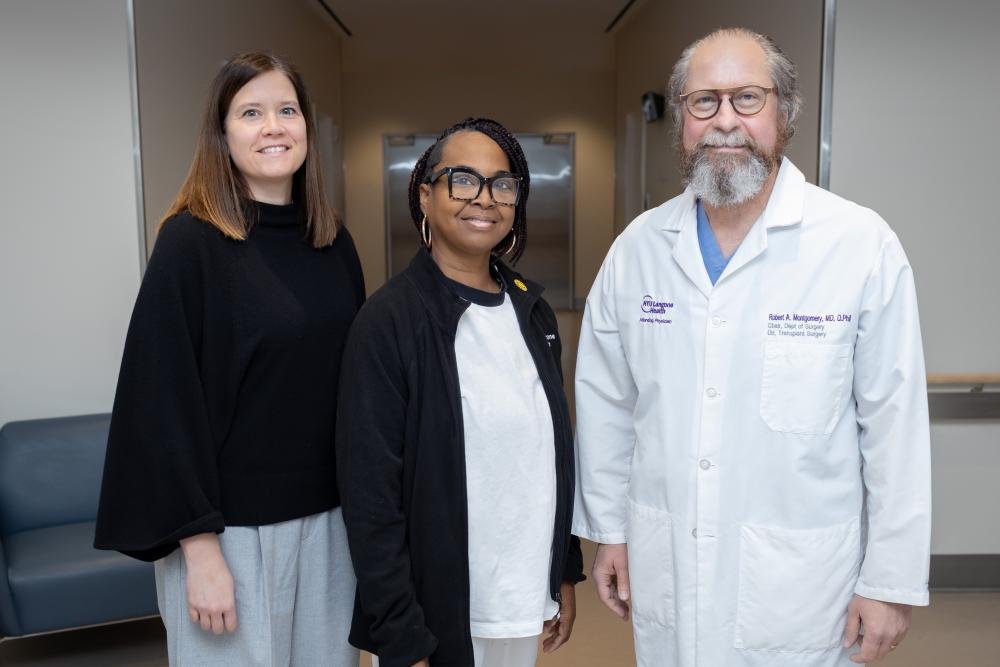

“It really allows us to get a better sense for what to expect from the clinical trials, which will involve patients who are in better general health,” Robert Montgomery, director of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute, told STAT in an interview. Looney’s progress will hold many lessons for what to expect in terms of the risk of rejection, how long the organs will last, and whether there’s anything the pig kidney can’t do that a human kidney does.

“We’ll have a longer event horizon to watch in order to get a better sense for how these organs are going to do long-term.” said Montgomery, who led the surgery.

It will take years of clinical trials to prove whether xenotransplantation could really work in patients — and be a viable solution to the nation’s organ shortage. Right now, more than 100,000 people are on the U.S. transplant waiting list — most of whom are in need of a kidney. Each year, thousands die waiting.

In September, eGenesis raised a fresh $191 million to advance its CRISPR’d pig kidneys toward human testing. CEO Mike Curtis told STAT he expects the company to ask the FDA for permission to start a formal trial in the second half of 2025.

A spokesman for United Therapeutics told STAT that it expects to file its own IND application to start a clinical trial for its 10-gene-edit kidney “shortly.”

For Looney, the next few weeks will be a critical time. Although testing prior to the procedure indicated that she had modest levels of so-called “xeno-antibodies” — immune molecules primed to recognize and react to the pig organ — a biopsy last week showed activation of her complement system. This is a network of proteins that enhances (or complements) the action of antibodies, but in the case of xenotransplant can give rise to damaging inflammation and clotting. “That could be an early indication that there could be some antibodies being released against the kidney,” Montgomery said.

To try to cool that down and prevent a potential rejection episode, Looney is now being administered an additional complement inhibitor. Her medical team said there are a number of additional medications available to reverse rejection if they begin to observe signs of it. The long-term goal is to eventually wean Looney off of the strongest immunosuppressive drugs as she adapts to the new organ, but she’ll always be on some.

Looney said she is eagerly awaiting being able to travel again and spend more time with her family and grandchildren. She also has another goal for her post-transplant life: “I want to go to Disneyworld,” she said, through laughter.