While athletes from Hong Kong have taken part in the Olympics since the interwar years, until 1948 they took part as Chinese national competitors under the Republic of China banner – not as a distinct regional entity. Teams and individuals from the People’s Republic of China, which came into existence in 1949, were recognised as PRC representative teams only after widespread diplomatic derecognition of the Nationalist government through the 1970s.

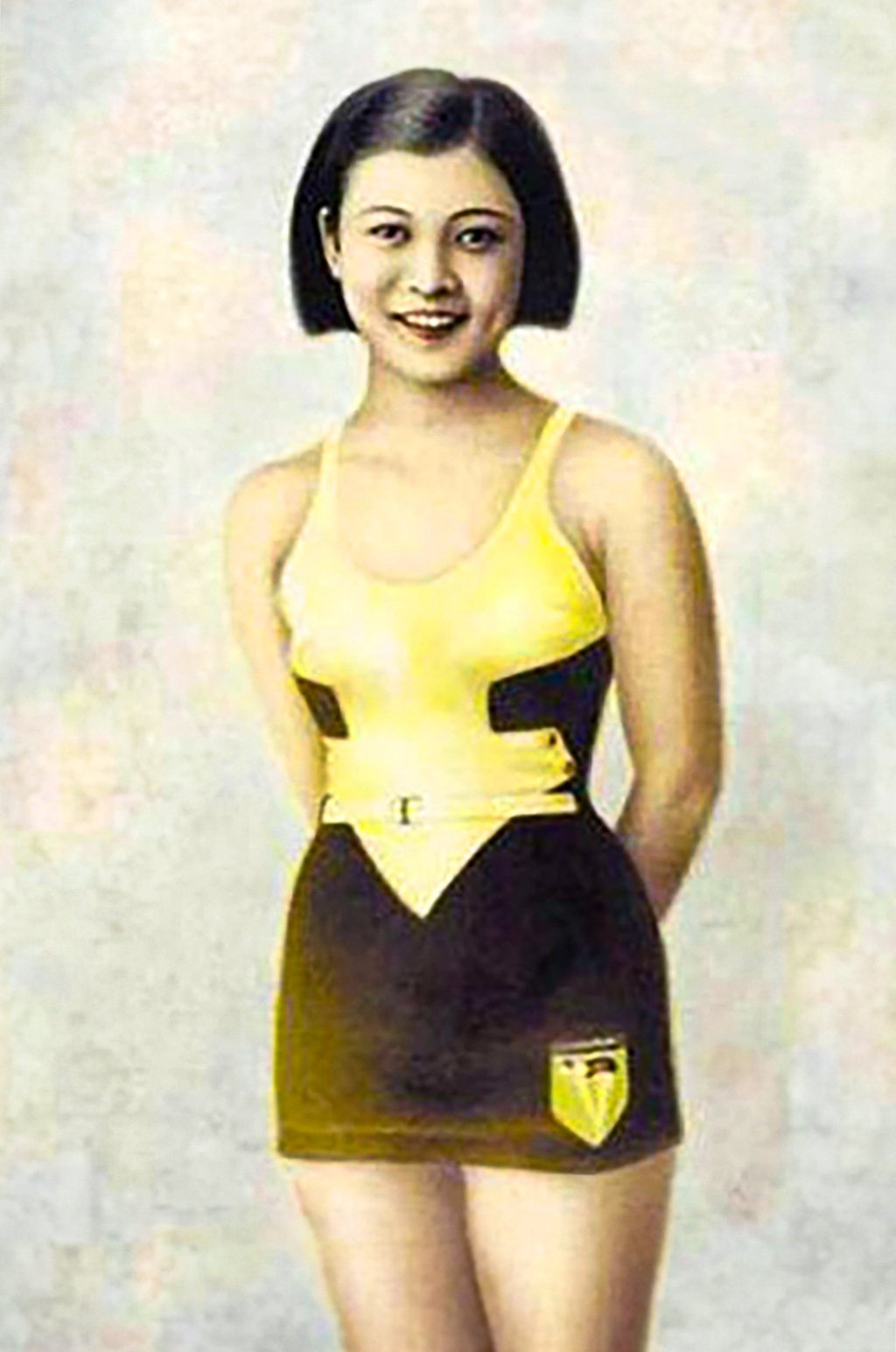

Yeung worked clandestinely in Japanese-occupied Hong Kong for Nationalist intelligence in 1942-43, before moving to Shanghai, where she continued these activities until the end of the war. Known for the rest of her life as “China’s mermaid”, after her post-war divorce from Tao and remarriage to an Indonesian-Chinese businessman, Yeung lived in Thailand for several years, returned to Hong Kong in 1953, subsequently emigrated to Vancouver, Canada, in 1978, and died there in 1982, after falling from a ladder.

But when did athletes directly begin to represent Hong Kong in its own right? The Amateur Sports Federation and Olympic Committee was formed in 1950. Recognised by the International Olympic Committee the following year, Hong Kong subsequently competed independently of Britain at the Games. In these instances, the Hong Kong flag was flown and the British national anthem – then also the local national anthem – played.

Despite ever-closer mainland integration, Hong Kong continues to send a separate team to the Olympics who compete under the SAR flag. That this extraordinary degree of autonomy still happens is ultimately due to one person’s stubborn determination; long-serving Urban Council chairman A. de O. Sales (Arnaldo de Oliveira Sales), who chaired the local Olympic Committee for decades.

Sales’ courage, quick thinking and decisive action during the 1972 Munich Olympics hostage-taking incident allowed Hong Kong athletes to escape unharmed. His forte, however, was in sports promotion. Although he was divisive and polarising in other areas, as a shrewd small-town political operator, he knew how to maintain his own power bases by playing both ends against the middle.

But not for nothing was Sales regarded as “the Mayor of Hong Kong”; whatever the circumstances, the wider interests of his hometown and its people always came first. In these very different days, such loyalties – sadly – cannot be automatically assumed.

A. de O. Sales died in Hong Kong, aged 100, in 2020.