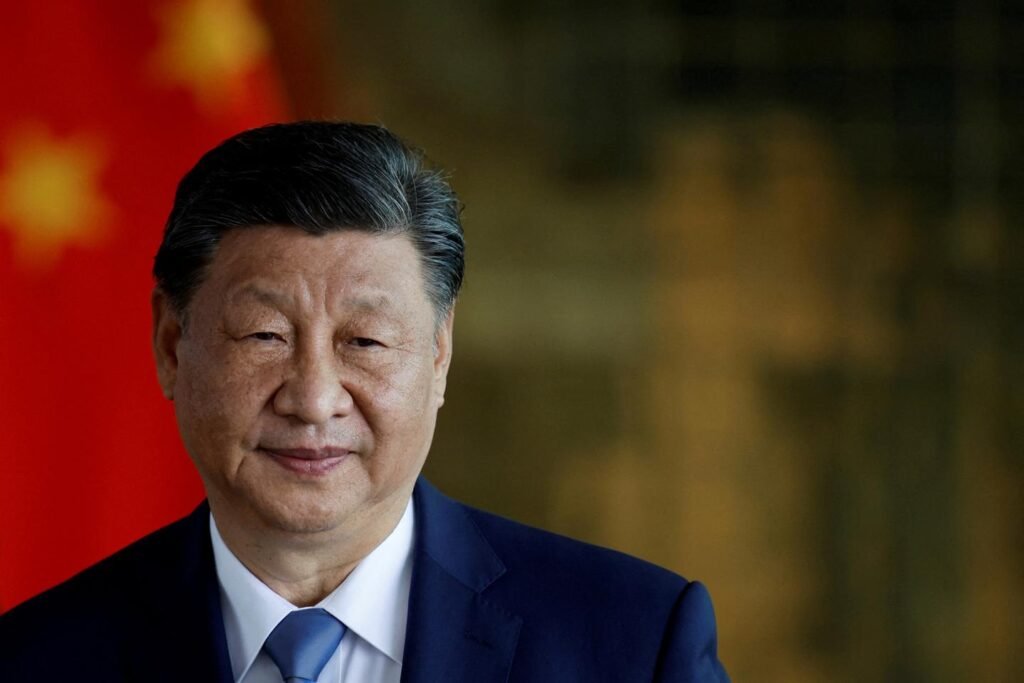

Xi Jinping knows how quickly power can slip away. As a child, he saw his father, Xi Zhongxun, then vice-premier of China, purged from the senior ranks of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) over his support for a historical novel. During the Cultural Revolution, when Xi was a teenager, his father was beaten and jailed as Mao Zedong urged the country’s youth to “bombard the headquarters” and root out the enemies of his revolution. Xi himself was denounced by his classmates and sent to work in the fields to be reformed through manual labour. His older half-sister killed herself during the decade-long campaign after apparently being “persecuted to death”.

The geopolitical environment that shaped the future Chinese leader was equally unforgiving. As a mid-ranking official in 1989, Xi saw the Berlin Wall torn down and the once mighty Soviet Union disintegrate. Where pro-democracy protests in China during this period were violently suppressed, Xi has blamed the Soviet leadership for allowing the neighbouring colossus to collapse without more of a fight. “Their ideals and convictions wavered,” Xi told party officials in 2012, shortly after becoming general secretary. “In the end nobody was a real man, nobody came out to resist.” He was determined not to make the same mistake.

From the outset, Xi’s rule has been defined by his focus on the party’s hold on power, and his own grip on the party, as he has sought to reassert the CCP’s control over all aspects of society. “His primal concern has long been the survival of the CCP itself, and his own position within it,” writes Kevin Rudd in On Xi Jinping. “This has been reinforced by his deep study of the Soviet Communist Party’s demise and his belief that this was brought about by the political and economic softening that occurred… under Mikhail Gorbachev.”

While the previous generation of Chinese leaders, and international observers, saw the extraordinary economic growth that came with the country’s shift to “reform and opening up” in the post-Mao era as an unparalleled success story, Xi was more circumspect. “The consistent tenor of his writings… has reflected Xi’s deep fear of two factors,” argues Rudd: “an increasingly corrupt relationship between the party and the private sector, and a rapidly expanding private sector writ large that increasingly exceeded the party’s capacity to control it politically.” He understood that intervening to restore the party’s ideological control would come at an economic cost, but he viewed that as a “price worth paying in exchange for the political objective of long-term party control he was seeking to secure”.

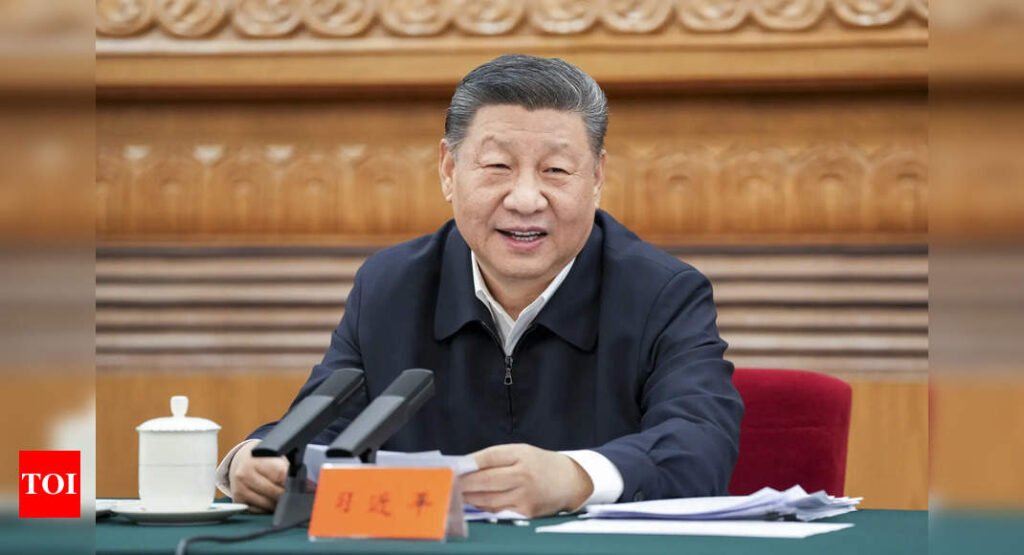

Fluent in both the Machiavellian aspects of political power and Mandarin, Rudd is uniquely positioned to undertake this study of Xi’s ideology. Rudd has been prime minister of Australia twice, as well as foreign minister, and is currently serving as the country’s ambassador to the US. He is perhaps the only leader to have spent significant time conversing with Xi, one on one, without the need for a translator. The book is based on his doctoral thesis at the University of Oxford, which he began in 2017 at the age of 59.

The resulting text, which is more than 600 pages long and includes close to 1,000 footnotes, is not exactly a beach read. Rudd acknowledges as much in the preface, with a suggested shortcut through the book for readers who prefer to spare themselves the detailed textual analysis of Xi’s prolific writings, and lengthy excerpts from his speeches on Marxist economic theory. Its scholarly discursions and sheer volume notwithstanding, On Xi Jinping is a remarkable feat of research, which delivers a clear, compelling argument as to what Xi really believes, and how he plans to remake China and the world.

For a leader who cultivates an image of inscrutability, Xi inhabits an “ideational universe” that is, Rudd warns, all too clear, and that we ignore his “clarity of ideological purpose at our peril”. Specifically, Rudd argues that Xi has “moved Chinese politics to the Leninist left, taken the Chinese economy to the Marxist left, and also shifted China to the nationalist right through a more assertive foreign and national security policy”, or what he calls “Marxist-Leninist nationalism”.

Xi’s rhetorical fealty to Marxism is clear. His speeches are laden with references to Marxist theory and praise for Marx as “the greatest thinker in human history”. But there has been more debate about his commitment to the emancipation of the proletariat in practice following his crackdowns on labour-rights activists and Marxist student groups, and his continuing tolerance for China’s stark income inequality. Xi is undeniably a Leninist, however, who clearly subscribes to the former Soviet leader’s view of the need to subordinate power to a rigidly disciplined vanguard party to lead the “dictatorship of the proletariat”.

When Xi assumed power in 2012, he was dismayed by a “lack of belief” among party members, decrying the “spiritually vapid” attitude of some officials and their misplaced faith in “the supremacy of money, the supremacy of fame and the supremacy of enjoyment”. Rehabilitating the language of “struggle” from the Mao era, Xi has exhorted young cadres instead to become true believers who serve the party’s interests first and “strive to become warriors who dare to fight and are good at fighting”. He has enshrined his ideology – formally known as “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” – in the constitution, removed term limits on the presidency, allowing him to stay in power indefinitely, and strengthened the party’s control over what Lenin called the “commanding heights” of society with what Rudd sees as an “almost fundamentalist ideological zeal”.

This is not a recipe for economic success. “The sheer weight of Leninist drag that an increasingly powerful party has on China’s once resilient, econocratic and technocratic elite cannot be underestimated,” writes Rudd. “At a practical level, the number of hours each week that economic decision-makers must now spend on ideological study and individual political survival detracts from the already complex task of managing the world’s second-largest economy.” Mindful of the danger of “committing an ideological or political error”, it is safer for Chinese officials to give feedback that is “ambiguous or, worse still, sycophantic”.

Xi has also embraced an assertive nationalism, partly driven, argues Rudd, “by a Chinese Marxist view that the inherent contradictions of the capitalist world are speeding its inevitable decline and putting fresh wind in the sails of China’s inevitable rise”. As Xi sees it, “with the Washington consensus in a state of collapse, the appeal of universal human rights diminished, and democracy in retreat, there is now an opportunity to fill an emerging vacuum for an acceptable global narrative capable of reaching across the developing world”. That assessment has presumably only been strengthened following Donald Trump’s return to power.

Where previous Chinese leaders adopted a more cautious approach to foreign policy – adhering to Deng Xiaoping’s aphorism calling for China to “hide our capacities and bide our time” – Xi has stressed the importance of “striving for achievement” instead. At the Party Congress in 2017, Xi declared it was time for China to “take centre stage”, telling Chinese ambassadors shortly afterwards that the world was facing “great changes unseen in a century”, with the trend towards “multi-polarisation” now “irreversible”. He has repeated his “great changes” formulation on multiple occasions since, including during his 2023 summit with Vladimir Putin in Moscow, when he assured the Russian leader that “we are the ones driving these changes together”.

Xi’s view that the world has reached a historic inflection point has profound implications for Taiwan. Like his predecessors, he has insisted that the self-ruling democracy must be brought under Beijing’s sovereignty and refused to rule out the use of force to do so. Rudd assesses Xi’s tenure as “the period of peak danger on the possibility of war over Taiwan”. He believes that the Chinese leader wants to take control of Taiwan by the end of his fourth term in 2032 if possible, with the only factors likely to dissuade him being “credible US, Taiwanese, and allied military deterrence – and Xi’s belief that there was a real risk of China losing any such engagement”.

Writing before Trump’s return to the White House, Rudd remarks that Xi would be “electric to possible opportunities in relation to Taiwan, if for example, a future US president were to withdraw military support for Ukraine’s defence against his ally, Vladimir Putin of Russia, thereby signalling a new and more isolationist world-view”. This is, more or less, what Trump is now threatening to do.

China faces its own domestic headwinds, with a looming demographic crisis, surging youth unemployment and a slowing economy. The last of these will only be exacerbated by Xi’s continuing focus on ideological discipline and Leninist control, and Trump’s threats to unleash a global trade war. The question is whether mounting challenges at home and growing uncertainty overseas will cause Xi to reconsider his objectives – such as seizing Taiwan – or if he will be seduced instead by the “great changes” he sees under way in the world and what he may well view as a unique opportunity to secure China’s pre-eminence and his own place in history. In that, determination may lie the seeds of his own downfall, with the consequences to be felt far beyond China’s borders.

On Xi Jinping: How Xi’s Marxist Nationalism is Shaping China and the World

Kevin Rudd

Oxford University Press, 624pp, £26.99

[See also: The long reign of the Caesars]

Content from our partners