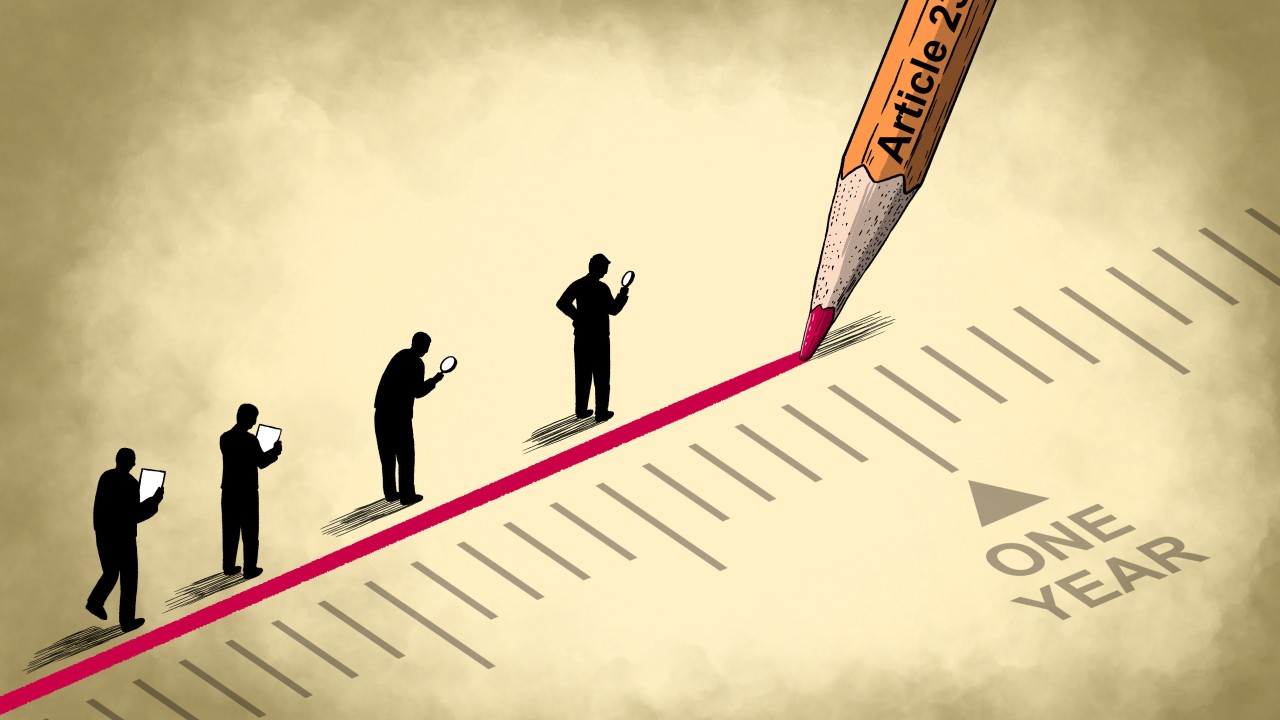

For Chan Po-ying of the League of Social Democrats, the immediate impact of Hong Kong’s local version of the national security law when it came into force a year ago came like a punch to her gut.

With the passage of the Safeguarding National Security Ordinance last March, she would have to wait 2¼ years longer before her husband “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung, a former lawmaker, would be freed. He had been jailed for six years and nine months last November in a landmark sedition trial.

Chan, who spent 50 years advocating for the city’s social equality and is currently the chairwoman of what was once deemed the radical wing of the pan-democratic camp, had thought Leung could be freed as early as 2027 after deducting his time in custody in the past four years as well as the discretionary one-third cut on his sentence for good conduct.

The new law, however, stipulates that a prisoner convicted of national security offences “must not be granted remission” unless authorities are satisfied the move will not compromise national security. Some activists have already been blocked from such early release after the new national security law was enacted.

“We know we should not bear any hope of early release, or it will only leave behind more disappointment,” 69-year-old Chan said.

“All I care about is that his days behind bars can be more fulfilling,” she added, referring to her jailed husband who turns 69 on Thursday.

Meanwhile, new law or not, her party continues to be about the only opposition group that still stages protests outside government headquarters.