China has turned a vast area of arid desert into a forest, and after decades of effort, it is today a huge carbon sink, according to new research. The Taklamakan Desert spans 337,000 square kilometres and is surrounded by high mountains that do not let moist air reach the area. This makes the condition unfavourable for any kind of vegetation. Yet, China started a project nearly 48 years ago to slow desertification. The Three-North Shelterbelt Program yielded results, and this desert now absorbs more carbon from the atmosphere than it emits. Billions of trees were planted around the Taklamakan’s edges as part of the ecological project. Study co-author Yuk Yung, a professor of planetary science at Caltech, told Live Science, this is the first time they have seen that ‘human-led intervention can effectively enhance carbon sequestration in even the most extreme arid landscapes.” This achievement shows that it is possible to turn a desert into a carbon sink.

“Great Green Wall” project and its success

The Taklamakan Desert has long been considered a “biological void” because over 95 per cent of it is covered in shifting sand. China started facing a problem in the 1950s when the country witnessed massive urbanisation. Natural land was converted to suit the changes, which led the desert to expand. This created conditions for more sandstorms, which blow away soil and deposit sand instead. The Three-North Shelterbelt Program, also known as the “Great Green Wall,” was kick-started in 1978. It targeted planting billions of trees around the margins of the Taklamakan and Gobi deserts by 2050. By 2024, it had sown more than 66 billion trees in northern China. Researchers say the vegetation has stabilised sand dunes and grown forest cover in the country. In 1949, this cover stood at 10 per cent of its area, and today it is at more than 25 per cent.

Recent research indicates that the Taklamakan Desert is acting as an unexpected carbon “sink,” with the green cover absorbing more CO2 than the desert releases. By analysing 25 years of ground observations, satellite data, and NOAA’s Carbon Tracker models, scientists have mapped a significant shift in the region’s carbon cycle. They published their results on January 19 in the journal PNAS. “Based on the results of this study, the Taklamakan Desert, although only around its rim, represents the first successful model demonstrating the possibility of transforming a desert into a carbon sink,” Yung said.

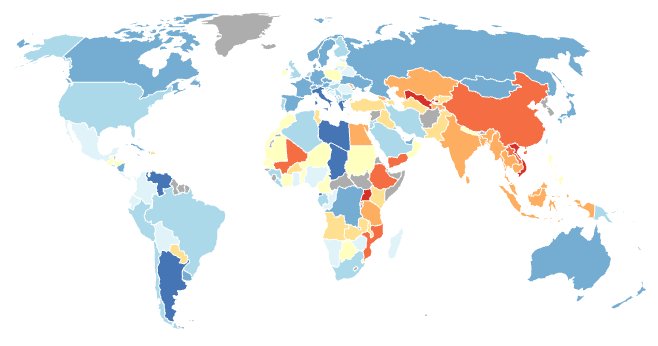

Scientists think the Great Green project can be a valuable model for other deser regions in the world. In comparison to the Taklamakan Desert, which spans 337,000 square kilometres, the Thar Desert in India is 264,091 square kilometres. Could trees turn Thar into a carbon sink?