They say that “the first step is always the hardest.” It’s the thought that tends to surface whenever I begin something new—photography, writing, or a skill I’m not sure I’m ready to learn. The hesitation is real. But after taking the leap, the floodgates open, and chances are you might find your next passion.

Take vibe coding, for example. When it first emerged, I convinced myself it might finally be the bridge between the ideas in my head and the websites and apps I’d never quite managed to build. Now, I wasn’t constrained by my lack of technical knowledge—AI would be my trusty assistant, guiding me on my quest to build digital solutions.

Decades ago, I dabbled in the development world, building HTML/CSS-powered websites and working with talented programmers and designers as a project manager to build dynamic, enterprise-scale apps. In the years since, I’ve largely

But there was a catch: Even with access to tools like Cursor, Replit, Lovable, Bolt, Base44, Vercel’s v0, Windsurf, GitHub Copilot, OpenAI’s Codex, Augment, and Anthropic’s Claude Code, I didn’t yet know what I wanted to build. That hesitation kept me from starting—if I was going to build something, I felt it needed to be meaningful, not just a small experiment.

That changed a few weeks ago when I attended a CTRL+ALT+CREATE workshop in Seattle, Washington, organized by community builder and creator Chris Pirillo. It was the spark I needed to jump-start my vibe-coding experience, with my first foray being a Grand Theft Auto-inspired game about oranges. It was a fun experience with the app developed using Google Gemini. However, it also surfaced for me issues that civilian developers may encounter—things I’ve only written about previously.

Still, from that workshop, my imagination began to grow, leading me to think about more complex apps I could build for real-world use. A conversation I had with my friend and entrepreneur, Greg Narain, led me to my next project: a site about OpenClaw.

Initially called Clawdbot, this open-source framework was created by Austrian developer Peter Steinberger in November 2025. It was designed to empower autonomous computer-use AI agents, letting them interact with software the way a human would through interfaces, files, and workflows. After receiving a cease-and-desist letter from Anthropic, the project would rebrand—not once, but twice, from Clawdbot to Moltbot, before settling on OpenClaw.

Steinberger’s project grew in popularity, even spawning a social network for OpenClaw-powered bots called Moltbook. Still, it wasn’t without controversy, with some researchers warning users not to grant the agents root access to their computers. Security concerns have forced Meta and other tech firms to restrict how employees can use OpenClaw.

Nevertheless, OpenClaw is a step forward in agentic evolution. While computer-use bots have existed before OpenClaw—Anthropic’s Claude, Google DeepMind, OpenAI’s Operator—this framework signifies accessibility and experimentation. Perhaps it’s representative of the world in which agents are speaking to other agents to help humans complete tasks.

Amid the flurry of activity over the past couple of weeks, Steinberger has since signed on with OpenAI, transitioning OpenClaw to an open-source foundation backed by ChatGPT’s creator.

Calling the pace of AI innovation rapid barely captures it. Trying to keep up with the evolution of agents can feel like a constant chase. OpenClaw is no exception, so to make sense of it, I vibe-coded an app—ClawBeat.co—to track the latest developments around Clawbot, Moltbot, OpenClaw, or whatever the project happens to be called.

Recognizing OpenClaw’s impact and the enormous attention it’s receiving, I felt a one-stop destination was needed to help find signal amid all of the AI noise. The site features a Techmeme-inspired news feed that pulls from not only traditional media but also creator platforms such as Substack and Medium. In addition, there’s a curated collection of YouTube videos and GitHub repositories. Lastly, the site displays a list of OpenClaw-related research papers from ArXiv, accompanied by summaries powered by Ai2’s Semantic Scholar API.

The idea was to create a site reflecting my interests in technology, curation, and journalism. Not only did I want to help people track what’s happening with OpenClaw, but I wanted to promote those covering this space, along with the builders. The aim was to create a destination that not only informs visitors about the latest advancements in OpenClaw but also inspires them to do something with the technology. It’s an app for all audiences, from technical developers to AI enthusiasts.

ClawBeat.co was done entirely by AI, though not as you may expect. Rather than subscribing to high-end vibe coding tools like Claude Code, I opted for lower-cost alternatives for budgetary reasons. While it meant extra work, it afforded me the chance to tinker, experiment, and try to understand what was happening under the hood.

Using ChatGPT, I crafted a series of editorial rules and policies for how content would be displayed and also how some features would behave. Those documents were then uploaded to Google’s AI Studio as part of my prompt to create my site’s front-end. After generating the files, I migrated them to Visual Studio Code, where I hoped to continue vibe coding using LLMs running locally through Ollama. Being largely non-technical, I wanted to experience the environment developers may typically use when vibe coding. Unfortunately, I wasn’t successful in this effort, so I had to pivot.

I turned to Google Gemini in the hopes of receiving step-by-step instructions on how ClawBeat would function. From there, I gradually built out my app, adding specific features prompt by prompt. Admittedly, this isn’t the ideal experience—I would have preferred AI to be more integrated with my development tools, but…it worked for me.

In any event, Gemini proved to be a good enough assistant to get this app to a good place for me to share with you today. AI has helped guide me from planning to production to distribution, specifically teaching me how to create a GitHub repository and set up a Vercel account. I’m pleased that I have a Minimal Viable Product (MVP) to unveil. This project has given me first-hand knowledge of technologies I’ve only had the pleasure of writing about before, and hopefully opens up more doors for me in the future.

What would you like to see from ClawBeat? Check it out at ClawBeat.co!

Share

Beyond launching this app, I took away a handful of practical lessons from this vibe coding process. Experienced coders will likely recognize them, but experiencing them firsthand gave them a different weight.

Seasoned developers may know this, but for casual and non-technical builders, choosing the AI model to help create your app can matter. While I predominantly used general-purpose Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT-5 and Google Gemini 3, I’m certain that I would have had significantly better prompt responses had I used Anthropic’s Claude Code or even coding-specific models from Qwen or DeepSeek.

Still, don’t think that you can only vibe code if you use a specific model—just expect more prompting and iteration if you’re using a general model versus a coding-specialized one.

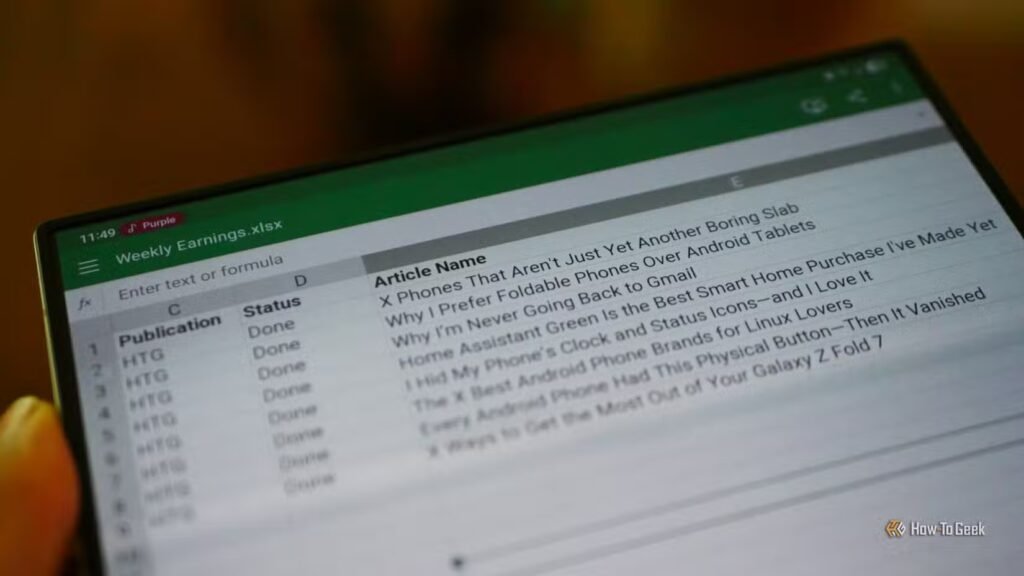

AI makes it easy to generate anything you want, but it comes with a cost. Using Google Gemini, there didn’t seem to be limits to what I could ask it to create. It would produce the code I wanted, and I would use it without much hesitation. I didn’t know where it would pull the data in from, or if a third-party resource is being used. The reality is that if you’re not careful, you can quickly accumulate complexity you don’t fully understand—or run headfirst into rate limits that interrupt your app’s flow and introduce unexpected costs.

When vibe coding an app, it’s easy to marvel at how good AI can quickly turn your idea into reality. However, it’s vital that developers don’t forget about data security. During its generation, the AI may not incorporate features that protect critical components, such as personal information, logins, and passwords used to access third-party systems, or API keys. In an earlier version, I noticed that some API keys were exposed in the code, so I instructed the AI to implement stronger security.

And that wasn’t the only time either. I’ve also had to double-check the AI’s suggestion to add specific data to my code.

As I prefaced earlier, the way I vibe-coded ClawBeat isn’t likely the way most developers would do it. But I don’t think there’s a consensus on how it should be done, right? Certainly, I’d likely get better coding if I integrated the model into my developer environment (e.g., VS Code) instead of relying on Google Gemini in another browser, where it doesn’t have eyes on what I’m working on.

And do I understand the code that was written? No. Copying and pasting what’s provided by Gemini into VS Code and praying it works is certainly a trust exercise. But perhaps the most significant lesson I learned from this activity is how to think through the app-building process. I needed to think through dependencies, inputs, expected behaviors, outputs, and edge cases. Moreover, what would ClawBeat need to do to be optimized for both web and mobile browsers?

Vibe coding doesn’t just teach people how to build features—it teaches them how to think in sequences, dependencies, and feedback loops, which is the essence of process design.

Throughout ClawBeat’s development, I found myself thinking less about how to code a feature and more about whether it felt possible to exist at all. For example, rather than trying to mentally understand how content clustering would work, I provided the AI with my request and was surprised when it returned a positive solution.

Vibe coding shifted my mindset from figuring out how something would work to simply deciding that it should exist—and then building toward that.

AI became my assistant, guiding me through all my questions as I navigated the process on my own—from making a pull request to understanding API costs, figuring out why a specific line of code was necessary, and grasping how everything worked.

Okay, so this isn’t a lesson learned, more like a proud personal accomplishment.

To be clear, this isn’t my first GitHub repository, but it is the first tied to a relatively complex app—at least for me. My earliest repo was for the Grand Theft Auto project that felt more like a vibe coding experiment. ClawBeat, on the other hand, is what I consider my first true production repository. That said, I’m excited to finally have a use for my GitHub account and be exposed to a critical tool used by developers everywhere.

Do I understand how to make pull requests now? Absolutely not, but with more practice, maybe I won’t be so dependent on AI to help me figure out how it all works.

With ClawBeat now in the wild, there’s a sense of relief in finally moving past the hesitation that kept me from trying vibe coding. It may sound strange, but as I think about how to evolve the app and feed new prompts into Google Gemini, the process has felt unexpectedly therapeutic, invigorating a passion that has long lain dormant.

Vibe coding was far from smooth sailing. Frustration surfaced often, and quitting crossed my mind more than once. Coding errors, misunderstood prompts, hallucinations, and disappearing features repeatedly tested my patience. There were more than a few times when I virtually yelled at the AI for providing inaccurate responses. Those moments forced me to question the hype—but they also became part of the learning curve.

What has your experience been with vibe coding? Tell me about your adventures.

Share