Sign up to our free IndyArts newsletter for all the latest entertainment news and reviews

Sign up to our free IndyArts newsletter

Sign up to our free IndyArts newsletter

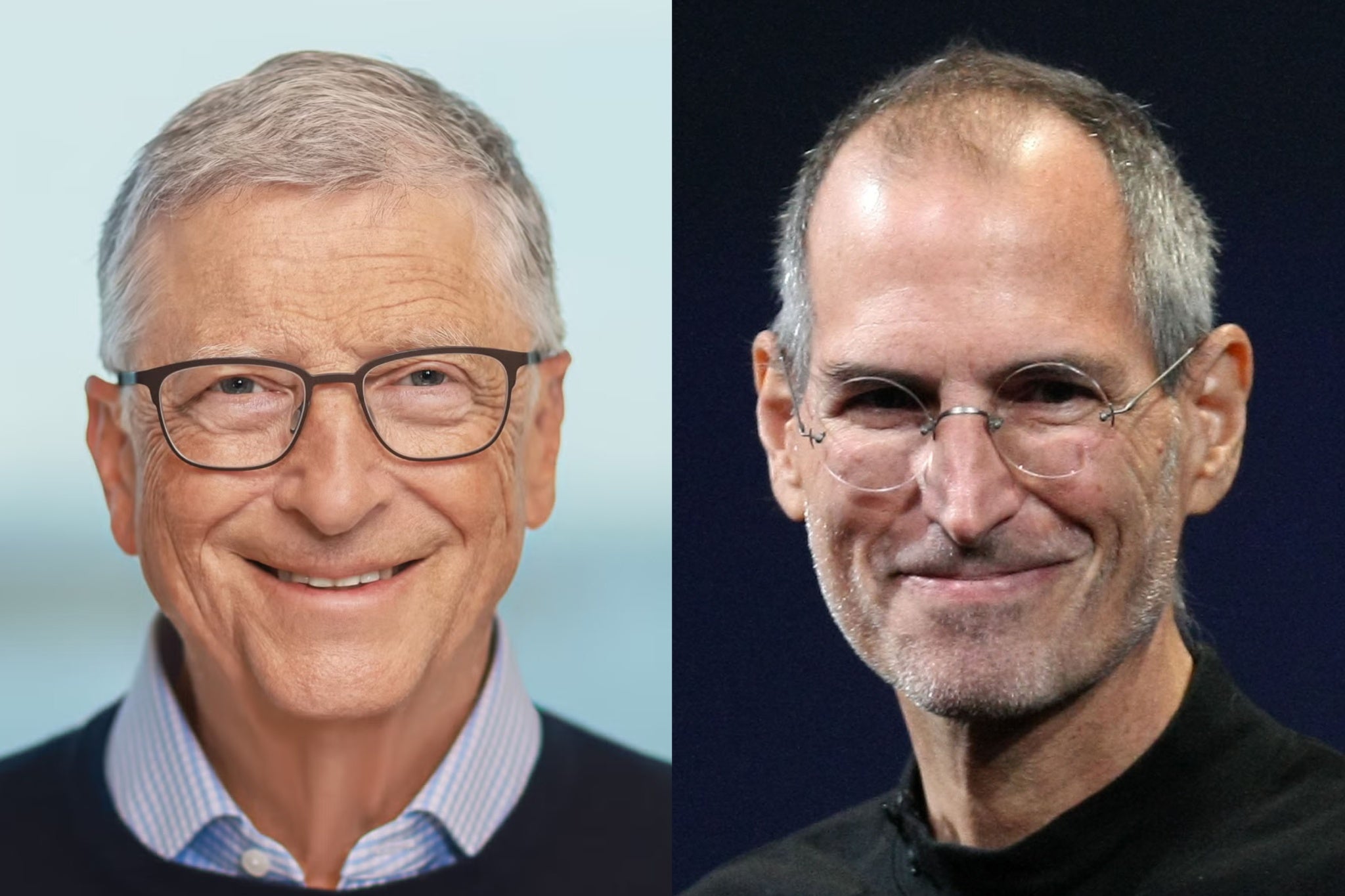

Bill Gates has opened up about his teenage experimentation with drugs including cannabis and LSD, and says he joked with Steve Jobs about taking “the wrong batch.”

The Microsoft co-founder and philanthropist, 69, writes about two acid trip experiences in his new memoir Source Code, published Tuesday (February 4).

Speaking to The Independent about what drew him to take the mind-altering substances, Gates said: “Because my personality is kind of optimistic, and I’m willing to take risks, I tried a lot of things.

“But another thing about my personality is that I like my mind to work and be very logical. So I stopped doing even marijuana early in my 20s just because it made my mind sloppy, either during or the day afterwards.”

He added: “I smoked pot in high school, but not because it did anything interesting. I thought maybe I would look cool and some girl would think that was interesting. It didn’t succeed, so I gave it up.”

Gates went on to say that former Apple CEO Steve Jobs, who didn’t know about his past drug use, teased him on the subject.

“Steve Jobs once said that he wished I’d take acid because then maybe I would have had more taste in my design of my products,” recalled Gates.

“My response to that was to say, ‘Look, I got the wrong batch.’ I got the coding batch, and this guy got the marketing-design batch, so good for him! Because his talents and mine, other than being kind of an energetic leader, and pushing the limits, they didn’t overlap much. He wouldn’t know what a line of code meant, and his ability to think about design and marketing and things like that… I envy those skills. I’m not in his league.”

Gates added that he was a fan of Michael Pollan’s book about psychedelic drugs, How To Change Your Mind, and is intrigued by the idea that they may have therapeutic uses. “The idea that some of these drugs that affect your mind might help with depression or OCD, I think that’s fascinating,” said Gates. “Of course, we have to be careful, and that’s very different than recreational usage.”

In Source Code, Gates recalls his first experience with LSD – and how it led to a nightmare visit to the dentist while he was still tripping. “Part of the trip was exhilarating, but I took the drug not realizing that I’d still be feeling its effects the next morning as I arrived at the orthodontist’s office for some long-scheduled dental surgery,” writes Gates.

“I sat gaping at my doctor’s face, his drill grinding away, unsure if what I was seeing and feeling was really happening. Am I going to jump out of this chair and just leave? I vowed that if I ever dropped acid again, I wouldn’t do it solo and I wouldn’t do it when I had plans for the next day, especially a dental procedure.”

Later in the book, Gates recounts another experience with LSD with future Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen and some friends, writing: “Paul had some LSD that we all dropped while watching Kung Fu”.

He says they went outside to look at the woods and traced the mathematical symbol ∃, meaning “there exists”, twice on the trunks of a car covered with dew. “The two backwards Es together, side by side, to him, to us, held some profound meaning,” recalls Gates. “‘Bill, see this. Existence exists,’ he said as we stared at the dewy car trunk. It was one of those moments that seem perfectly cosmic at the time and purely silly once the acid wears off.”

Gates says in the book that it was the fear of damaging his memory that finally persuaded him never to take the drug again. “On a computer you can delete a file and even wipe out all of your stored data,” he remembers thinking. “Since the brain is just a sophisticated computer, I thought, Hey, maybe I can command my brain to zero out all my memories? But then I got worried that testing that notion might actually set it irrevocably into motion.”

In an exclusive extract from his new memoir published by The Independent, Gates opens up about the impact that being sent to therapy as a young child had on his life.