China news correspondent, Lianhe Zaobao

More than 50 years after Apollo, the US races back to the moon amid growing fears that China could beat it. What was once a symbol of exploration is now a high-stakes arena of strategic rivalry. Lianhe Zaobao’s correspondent Yush Chau finds out more.

When American astronauts stepped onto the moon in 1969, it marked a high point of human spaceflight. More than half a century on, the US — the sole nation to have conducted crewed lunar landings — is racing back, spurred by a growing fear that China could get there first.

“If we fall behind — if we make a mistake — we may never catch up, and the consequences could shift the balance of power here on Earth.” — Jared Isaacman, Nominee for the role of administrator of the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)

The stakes of losing the moon

From the first lunar landing by Apollo 11 in 1969 to the final mission of Apollo 17 in 1972, a total of 12 American astronauts left their footprints on the moon. However, after gaining the upper hand in the space race with the Soviet Union, enthusiasm within the US for costly and high-risk crewed lunar missions waned, and the Apollo programme was ultimately terminated.

In 2017, during his first term, US President Donald Trump signed Space Policy Directive-1, announcing that American astronauts would return to the moon and eventually travel to Mars. Whether in the Trump 1.0 or 2.0 era, the US has consistently regarded China as its primary competitor in space, and this competition has continued to intensify.

At a Senate confirmation hearing on 3 December this year, Jared Isaacman, the nominee for the role of administrator of the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), stressed that the US must return to the moon before its “great rival”, and plans to establish a permanent base there to explore and assess the moon’s economic, scientific, and national security value.

At the hearing, Isaacman also warned, “If we fall behind — if we make a mistake — we may never catch up, and the consequences could shift the balance of power here on Earth.”

The following day, the Aerospace Subcommittee of the US House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology held a hearing on “Assessing China’s Space Rise and the Risks to US Leadership”. When asked whether NASA could return to the moon as planned before China, several experts responded candidly: “No, I am very pessimistic”; “Worried”; “Maybe”; and “No possible way… with the present plan.”

Clayton Swope, deputy director of the Space Security Project at the US think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies, said at the hearing that while China has mostly copied the US space playbook, it is now doing things that no one else has done.

Chinese authorities have recently reaffirmed that the goal of landing Chinese astronauts on the moon before 2030 “remains unchanged”.

Three pioneering Chinese aerospace achievements

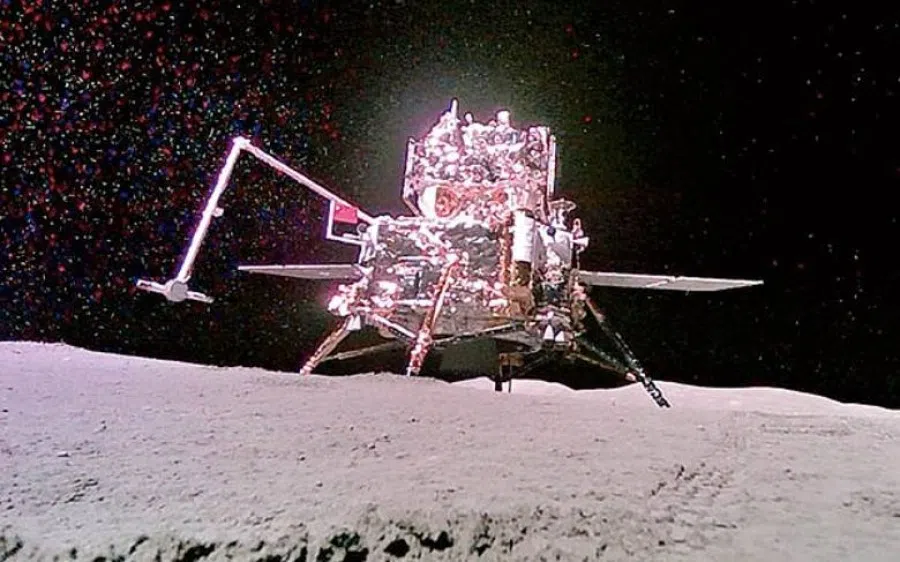

He listed three major achievements of China’s space programme: the world’s first unmanned sample return from the far side of the moon; in-orbit refuelling of a satellite in geostationary orbit; and the operation of the world’s first — and so far only — communications satellite at the Earth-moon L2 point.

The Earth-moon L2 point lies on the extension of the line from the Earth through the moon, about 65,000 kilometres from the moon. At this location, the gravitational forces of the Earth and the moon are balanced, allowing spacecraft to maintain their position using relatively little fuel.

The US has named its lunar return programme“Artemis”, after the twin sister of Apollo, the Greek god of the Sun. Coincidentally, China’s lunar exploration programme, launched in 2004, is named after Chang’e, a figure from Chinese mythology. The programme is divided into three phases: uncrewed lunar exploration, crewed lunar landings, and the establishment of a lunar base. Over the past two decades, China has launched the Chang’e-1 through Chang’e-6 probes, with Chang’e-6 achieving an uncrewed sample return from the far side of the moon last year.

China has fully launched its crewed lunar landing programme since 2023, and Chinese authorities have recently reaffirmed that the goal of landing Chinese astronauts on the moon before 2030 “remains unchanged”.

At a press conference on 30 October for the Shenzhou-21 crewed spaceflight mission, Zhang Jingbo, spokesperson for China’s Manned Space Program, said that major work at the preliminary design stage has been completed for key flight systems, including the Long March 10 launch vehicle, the Mengzhou crewed spacecraft, the Lanyue lunar lander, the Wangyu lunar spacesuit and the Tansuo manned lunar rover.

He also noted that the science research and application systems have completed payload scheme designs for each flight mission, and that construction and development of ground systems — such as launch sites, tracking and control communications, and landing zones — are being accelerated.

Increasing likelihood of China landing on moon first

By contrast, the US’s Artemis programme was originally scheduled to return humans to the moon by the end of this year, but has been repeatedly delayed due to technical and budgetary issues.

According to NASA’s latest timeline, the Artemis II mission — carrying astronauts on a crewed lunar flyby — is expected to take place as early as February next year, while the Artemis III mission, involving a crewed lunar landing, is slated for mid-2027.

NASA’s plans rely heavily on private enterprises. For example, the lunar lander is to be developed by US space company SpaceX, based on its Starship spacecraft. However, internal SpaceX documents revealed by US media outlet Politico indicate that Starship will not be ready for a crewed lunar landing until at least September 2028. This suggests that, under the latest timelines, it is increasingly likely that China will reach the moon before the US.

… if delays to the Artemis program continue while China maintains its planned pace, Beijing could successfully reverse the political narrative… — Zhao Tong, Senior Fellow, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Zhao Tong, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told Lianhe Zaobao in an interview that if delays to the Artemis program continue while China maintains its planned pace, Beijing could successfully reverse the political narrative: the US programme would appear stalled by political constraints and industrial bottlenecks, while China steadily delivers on its commitments.

In his view, China’s push for a crewed lunar landing is not merely a scientific endeavour; it also serves national prestige and political objectives, and functions as a powerful driver of industrial policy — “spurring breakthroughs in advanced materials, autonomous systems, artificial intelligence, and high-end manufacturing, with spillover benefits for both civilian and defence industries.”

China-US competition for lunar governance influence

In fact, around their respective crewed lunar programmes, China and the US are actively courting partners, competing for influence over the governance of the moon. The lunar south pole is regarded by both countries as a strategic location: the water ice believed to be present there would be a critical resource for future bases and a springboard for deep-space exploration.

In 2020, the US launched the Artemis Accords. To date, 59 countries have signed on. Some analysts argue that the Accords’ advocacy of delineating “safety zones” is aimed directly at securing scarce lunar resources and ensuring that exploration and resource extraction are not disrupted by other countries.

In 2021, China, a non-signatory of the Artemis Accords, jointly launched the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) initiative with Russia. As of April 2025, 17 countries and international organisations, and more than 50 research institutions have signed up for the ILRS.

At present, China is advancing its vision of becoming a space power through a whole-of-nation approach, with both crewed lunar missions and commercial spaceflight developing rapidly in parallel.

China, by contrast, has not signed the Accords. Instead, it jointly launched the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) with Russia in 2021. As of April this year, 17 countries and international organisations, along with more than 50 research institutions, have joined the initiative.

Zhao believes that if China is the first to achieve a crewed lunar landing in this competition, the International Lunar Research Station could become a new platform — following the Belt and Road Initiative and digital infrastructure — for China to attract international partners, particularly developing countries that harbour doubts about Western leadership yet are eager to participate in high-end space cooperation.

China faces key aerospace technical obstacles in overtaking US

At present, China is advancing its vision of becoming a space power through a whole-of-nation approach, with both crewed lunar missions and commercial spaceflight developing rapidly in parallel.

The 15th Five-Year Plan (2026-2030) policy recommendations released in October this year for the first time explicitly called for accelerating the building of a “space power” and promoting the development of strategic emerging industrial clusters such as aerospace. Commercial spaceflight has also been written into the government work report for two consecutive years since 2024.

Spurred by supportive policies, social capital has poured into the commercial space sector over the past decade, with over 600 Chinese commercial space companies today. In November this year, the China National Space Administration established a Commercial Spaceflight Department and released an action plan to promote the high-quality and safe development of commercial spaceflight, outlining 22 specific measures.

Continuity in Chinese aerospace plans, while electoral cycles sway US policies

Experts interviewed noted that China and the US each have distinct advantages in their space competition. China benefits from a clear set of goals and a long-term, stable policy framework, while the US maintains its lead through more innovative private space companies, a mature research ecosystem and a broad network of allies.

Qiu Mingda, a senior China analyst at Eurasia Group, pointed out that China’s centralised political system lends greater continuity to its space planning, whereas US policies are more prone to shifts driven by election cycles.

However, even if China manages to take the lead over the US in crewed lunar landings, it still faces the challenge of overcoming several key technological hurdles before it can achieve comprehensive superiority in the space domain.

Andy Mok, a senior research fellow at the Centre for China and Globalisation (CCG), assessed that during the 15th Five-Year Plan period China may be able to compete on equal footing with the US in Earth–moon transportation and lunar missions. “Closing the gap in key areas is very realistic, but overtaking the US entirely is unlikely.”

Carnegie’s Zhao also said candidly that even if China pulls ahead at certain symbolic milestones — such as achieving a crewed lunar landing first or surpassing the US in the number of rocket launches in a given year — the likelihood of comprehensively overtaking the US before the conclusion of the 15th Five-Year Plan remains low.

According to US aerospace news website space.com, China has carried out 70 rocket launches so far this year, a record high. This figure, however, is still well below the US’s 150 launches. Most US launches are conducted by SpaceX using its reusable Falcon 9 rockets, primarily to deploy the company’s low-Earth-orbit (LEO) satellites for its Starlink internet constellation.

A shortage of launch vehicles relative to the number of satellites, and insufficient launch capacity, remain major bottlenecks. Reusable rockets are widely seen as the key to breaking through these constraints.

LEO satellite internet constellations are also one of the main arenas of China-US space competition. By leveraging reusable boosters to significantly reduce launch costs, SpaceX has consolidated its dominant position in both the global commercial launch market and the LEO satellite internet sector. Starlink plans to deploy 42,000 satellites; around 9,300 are already in orbit, accounting for more than 65% of the global total.

China views Starlink as a potential military threat and is advancing its own LEO satellite internet initiatives — the Guowang and Qianfan constellations — with a combined planned total of nearly 28,000 satellites. However, launch progress has been constrained. As of November, the two constellations had launched only about 230 satellites. A shortage of launch vehicles relative to the number of satellites, and insufficient launch capacity, remain major bottlenecks. Reusable rockets are widely seen as the key to breaking through these constraints.

China is still in the development phase when it comes to reusable rocket technology. On 3 December this year, private aerospace company LandSpace successfully launched its domestically developed reusable rocket, Zhuque-3, into orbit on its maiden flight. However, the first-stage recovery failed, indicating that the relevant technologies are not yet mature.

Inevitable militarisation of space will impact power balance on Earth

The space race between China and the US involves not only the exploration of outer space, but also has profound implications for the global security landscape. Because satellites are indispensable to communications, reconnaissance, and command-and-control systems, space has become a key frontline in the two countries’ military competition.

The Russia-Ukraine war has further underscored the dual-use nature of space technology for both civilian and military purposes. After the outbreak of the war in 2022, Ukraine sought support from SpaceX founder Elon Musk for access to Starlink. The satellite network quickly played a critical role in battlefield communications and drone operations, demonstrating that space capabilities have become a core pillar of modern warfare.

In September this year, the US Council on Foreign Relations published an article simulating scenarios of a Taiwan Strait conflict, arguing that if mainland China were to take military action against Taiwan, the opening strike might come from space rather than the sea or air.

The article described how China’s ground-based laser weapons could disable US satellites, while Chinese satellites with manoeuvring capabilities could interfere with or destroy key satellites relied upon by the US military, including systems used for precision-strike navigation and troop communications. If these systems were compromised, US forces could be fighting blind.

The US formally established the US Space Force (USSF) in 2019. Its chief of space operations, Chance Saltzman, warned in April this year that China may view counter-space operations as a means to deter US involvement in regional conflicts, adding that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) routinely employs radio-frequency jamming in its exercises and drills.

“The real danger is not deliberate aggression, but uncontrolled competition.” — Andy Mok, Senior Research Fellow, Centre for China and Globalisation (CCG)

According to the USSF’s Space Threat Fact Sheet, as of July this year China has more than 1,189 satellites in orbit, of which 510 are used for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance.

China, for its part, has criticised the US for hyping up a “China space threat” narrative, stressing that it upholds the peaceful use of outer space and opposes the weaponisation of space.

In June this year, PLA Daily, the official newspaper of China’s Central Military Commission, published an article criticising the US for accelerating the development of its Space Force, arguing that this undermines global strategic stability, triggers a space arms race, and increases the risk of conflict in space.

However, Zhao Tong pointed out that the People’s Liberation Army has already incorporated anti-satellite weapons, co-orbital capabilities, electronic interference and cyberattacks into its operational system.

China’s 2007 anti-satellite test, while controversial for generating large amounts of space debris, also demonstrated its space strike capabilities. The establishment of the Strategic Support Force in 2015, along with military reforms in 2024, likewise reflects the Chinese military’s efforts to integrate space, information and cyber warfare capabilities.

Some academics are also concerned that if China-US space competition evolves into a zero-sum game, the consequences could be difficult for either side to bear. CCG’s Andy Mok warned that as both sides pursue parity in combat capabilities, the risk of miscalculation is steadily increasing: “The real danger is not deliberate aggression, but uncontrolled competition.”