As winter cools Dhaka, politics is heating up fast.

The funeral of Khaleda Zia, the rise of her son Tarique Rahman, and elections scheduled for February 2026 have pushed Bangladesh into a moment of reckoning. It feels uncannily like another turning point—one that echoes the upheavals of the early 1970s.

Back then, the fate of Bangladesh was shaped by global powers playing Cold War chess. Pakistan, India, the United States and the Soviet Union dominate the popular memory of 1971. But one actor is often quietly pushed to the margins of that story: China. That omission is no longer affordable. Today, China is Bangladesh’s largest trading partner and its most important defence supplier. What Beijing does—or chooses not to do—matters enormously.

There is an old warning in the Bhagavad Gita: when memory fades, wisdom collapses, and with it, sovereignty. For Bangladesh in 2026, this is less philosophy than practical advice. Forgetting how China behaved during the country’s birth carries real costs.

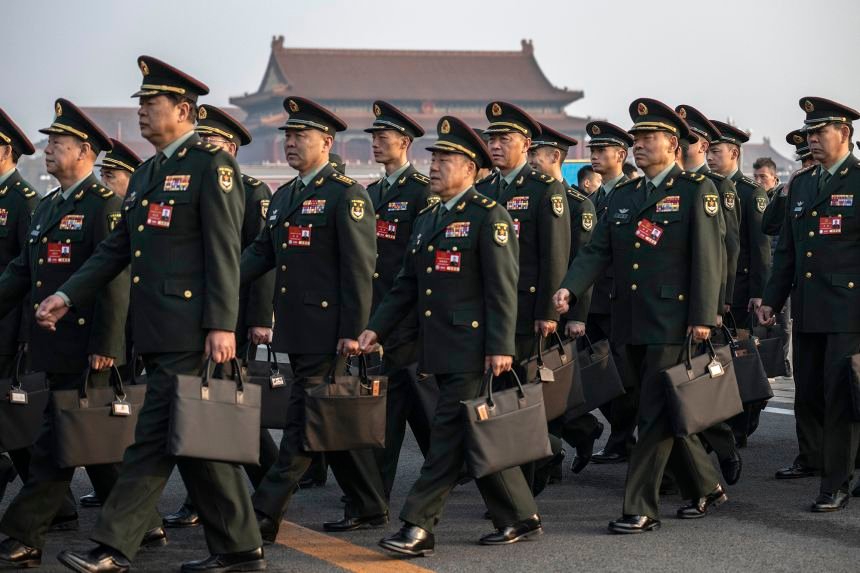

China did not support Bangladesh’s liberation. It opposed it. While genocide unfolded in East Pakistan in March 1971, Beijing framed the crisis as Pakistan’s “internal affair”. Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai assured Islamabad of support and warned against outside “interference”. China backed this position with money, military advisers and diplomatic cover for Pakistan—while remaining silent on mass killings.

When war finally broke out in December 1971, China moved from quiet backing to open obstruction. Having just taken its seat at the United Nations, Beijing used its new clout to block international moves toward recognising Bangladesh. Later, it cast its first-ever veto in the UN Security Council to stop Bangladesh’s entry into the UN. Recognition came only in 1975—after the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

This was not sentiment or ideology. It was pure realpolitik. Pakistan mattered more to China than Bengali lives or self-determination. The Indo-Soviet Friendship Treaty limited Beijing’s options militarily, but diplomatically, it did everything it could to deny legitimacy to Bangladesh’s struggle.

Fast forward to today, and the contrast is stark. Bangladesh is no longer a fragile newborn state. It has grown, industrialised, reduced poverty and claimed a serious regional role. China, for its part, has invested heavily in Bangladesh’s economy and military. The relationship now looks pragmatic, even warm.

Yet history has a way of resurfacing when least convenient. Recent signals—unfriendly rhetoric about India’s northeast, unease over minority safety within Bangladesh, and rising regional tensions—have set off alarm bells in New Delhi. For India, stability on its eastern flank is non-negotiable. For Bangladesh, internal cohesion and external balance are equally vital.

This is where memory matters. China’s interests have not suddenly become sentimental. They remain transactional. Bangladesh is important to Beijing as a strategic partner, a market, and a foothold—not as a moral cause. That does not make engagement with China wrong. It makes caution essential.

The lesson of 1971 is not that Bangladesh should distrust everyone or relive old grievances. It is simpler: power remembers its interests, even when others forget. A nation born out of resistance to oppression cannot afford historical amnesia when navigating great-power politics.

As Bangladesh heads into a decisive election, the real test is not choosing sides but avoiding captivity to any single one. Smart diplomacy today means balancing relations with China, India, and others—without becoming a piece on someone else’s board.

Bangladesh is no longer a pawn. But even pivotal players must remember how the game was once played, who moved which piece, and why.