Network analysis

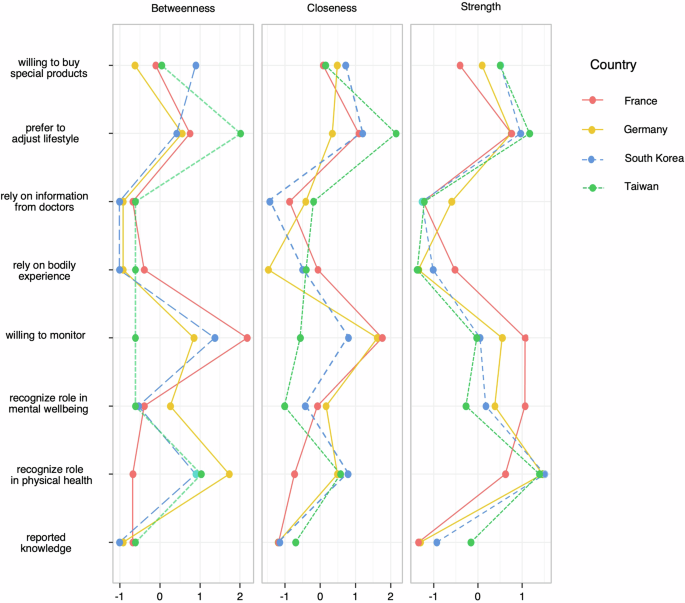

We performed the network analysis including centrality indices measures for the entire dataset (Supplementary Figs. 1–2, see Supplementary Information) and per country (Supplementary Fig. 3 and 1). Non-parametric bootstrapped CIs remained consistent with the original samples both for the overall network and per country (Supplementary Fig. 3 and 6). The case-dropping subset bootstrapping showed stable centrality indices after dropping up to 75% of the sample across all networks. The CS-Cs were above 0.8 for the aggregated network (Supplementary Fig. 4), above 0.7 for France and Germany, and even the lowest CS-Cs (closeness and betweenness for South Korea and Taiwan) were above 0.5 (Supplementary Fig. 6).

The plots of the estimated network for Asian countries demonstrate more connections between the edges, whereas the plots for France and especially Germany exhibit lower global network connectivity (Supplementary Fig. 3). Recognizing the role of HM in one’s physical health is quantified as the first node in strength and the second in betweenness. Preference to adjust lifestyle to sustain/improve the health of one’s microbiome is the second strongest node and the first for both closeness and betweenness measures. The second prominent node for closeness is willingness to monitor one’s microbiome’s health. Plots per country (Fig. 1) show some variations. For example, in France, the strongest nodes were the willingness to monitor one’s microbiome and the recognition of the HM’s role in mental wellbeing.

How people learn about HM

The mean self-reported familiarity with HM (we interchangeably refer to it as “knowledge” here) was 3.31 (SD = 1.58) on a scale of 7 (1 indicating “no knowledge at all”, 4 “not sure” and 7 “a lot of knowledge”). The average score was lowest for Germany (M = 2.86; SD = 1.53), followed by France (M = 3.08; SD = 1.67). Taiwan and South Korea had somewhat higher scores (M = 3.63; SD = 1.59 and M = 3.65; SD = 1.38, respectively). In France and Germany, about a quarter of respondents reported to have no knowledge regarding the HM at all, which was ca. 9% and 12% in South Korea and Taiwan, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Respondents with higher education reported somewhat more knowledge of HM than those with lower education (M = 3.63; SD = 1.52 vs. M = 3.11; SD = 1.59). The mean knowledge reported by participants working in healthcare or life sciences (11% of all respondents) was 4.28 (SD = 1.52) vs. 3.19 by the others (SD = 1.55). Individuals who were 55–64 and especially 65+ years old reported the lowest knowledge (M = 3.25; SD = 1.55 and M = 2.94; SD = 1.50, respectively). Self-reported knowledge was also low among participants who reported to believe neither in God, nor in any spirit or life force (M = 3.05; SD = 1.53).

Table 1 presents the main sources of information on HM reported by the participants. In all four countries, television belonged to the top three information sources. Other sources included healthcare professionals (except for South Korea), internet websites/blogs (except for Taiwan), press for South Korea and social media for Taiwan. The least mentioned sources included companies offering special products (especially, for France and Germany), social media in the European countries, and family/friends in Asian countries.

Estimated role of HM in health and wellbeing

Respondents were asked how much they believed their microbiome to affect their physical health and mental wellbeing. On a 7-point scale (1 indicating “not at all”, 4 “not sure” and 7 “very much so”) the mean was 4.97 for physical health (SD = 1.3) and 4.59 for mental wellbeing (SD = 1.33). Supplementary Figs. 6–9 show the score distribution per country and between countries. Most respondents acknowledged the importance of HM for their physical health (from 54% in France to 65% in the Asian countries), whereas about 30–33% of respondents in each country were unsure. Less people recognized the role HM may play in their mental wellbeing (from 45% in France to 51% in South Korea). The number of participants unsure about it varied between 31% in France and 41–42% in other countries.

Among the age groups, acknowledging the role of HM for one’s health was highest for the 55–64-year-olds (M = 5.09; SD = 1.24 for physical health and M = 4.74; SD = 1.28 for mental wellbeing). Higher educated participants recognized the role of HM more (M = 5.17; SD = 1.19 for physical health and M = 4.73; SD = 1.23 for mental wellbeing). Being a non-believer was associated with somewhat lower scores (M = 4.7; SD = 4.62 and M = 4.29; SD = 4.2, respectively).

Preferences in monitoring and sustaining HM health

We asked the participants to rate their willingness to monitor the health of their microbiome (on a scale of 7, 1 indicating “not at all”, 4 “neutral” and 7 “extremely”). The majority of participants expressed willingness to do this (M = 4.68, SD = 1.45). Respondents in Europe demonstrated a higher readiness than those in Asia (56–57% vs. 49–51%). Supplementary Figs. 10–11 show the score distribution per country and among the countries.

Participants rated how much they agreed (on a scale of 7, 1 indicating “strongly disagree”, 4 “neutral” and 7 “strongly agree”) that to estimate the health of their microbiome they relied on their own feelings and bodily experiences (M = 4.63, SD = 1.29) vs. information and techniques from healthcare professionals (M = 4.72, SD = 1.38). Trust in one’s bodily experience as indicator of healthy microbiome ranged between 44% in South Korea and 61% in France, whereas relying on doctors’ tips ranged between 46% in Germany and 57% in France and Taiwan. Score distributions per country and between countries are presented in Supplementary Figs. 12–15.

To sustain and improve the health of one’s microbiome the respondents showed willingness to adjust their lifestyle such as diet and exercise (M = 5.08, SD = 1.31) as well as to buy special products (M = 4.43, SD = 1.49). In Taiwan and France as many as 70–71% of the respondents would be willing to adjust their lifestyle (M = 5.29, SD = 1.26 and M = 5.22, SD = 1.37, respectively). For Germany and South Korea, it was 58–60%. Interest in special products was somewhat higher in Asia (51–54% vs. 40–42% in Europe). Supplementary Figs. 16–19 show score distributions on these questions.

The participants with higher education expressed the highest willingness to monitor their microbiome health (M = 4.8, SD = 1.32), relied most both on their bodily experience and doctor’s advice (M = 4.71, SD = 1.26 and M = 4.85, SD = 1.32), and showed most readiness to adjust their lifestyle and to buy special products (M = 5.3, SD = 1.2 and M = 4.7, SD = 1.4). The respondents working in healthcare and life sciences reported higher scores than the individuals in other professional fields: their mean score for being ready to keep an eye on one’s microbiome health was 5.13 (SD = 1.36), for relying on one’s bodily experience and doctor’s tips 5.02 and 5.06 (SD = 1.2.8 in both cases), and 5.45 and 4.88, respectively, for lifestyle adjustments and buying special products (SD = 1.23 and SD = 1.5). The scores reported by non-believers were lower in all areas: the mean score for willingness to observe one’s microbiome health was 4.44 (SD = 1.47), for attuning to one’s feelings and to doctor’s advice 4.4 and 4.55 (SD = 1.31 and SD = 1.42), and for intending to change one’s lifestyle or buy special products 4.79 and 4.06, respectively (SD = 1.36 and SD = 1.52).

Environmental perceptions related to HM

A paired samples t-test shows a slight positive shift in perceptions of microorganisms following a moment of reflection on the HM (M = 4.71, SD = 1.24) compared to baseline (M = 4.04, SD = 1.36, T = -22.55, p < 0.001). The effect size was rather small (Cohen’s d of 0.42). A statistically significant effect (p < 0.001) was observed for each of the four countries. France had the largest change in mean score (from M = 3.46, SD = 0.06 to M = 4.65, SD = 0.04) with a moderate effect size of 0.67. In Germany the score increased from M = 4.13 (SD = 1.08) to M = 4.66 (SD = 1.26). In South Korea and Taiwan, the rating increased from M = 4.25 (SD = 1.32) to M = 4.74 (SD = 1.2) and from M = 4.32 (SD = 1.28) to M = 4.79 (SD = 1.31) respectively. The effect sizes for Germany, South Korea and Taiwan were small (0.36, 0.32 and 0.36, respectively). An overview of mean changes across the four countries is presented in Supplementary Fig. 22.

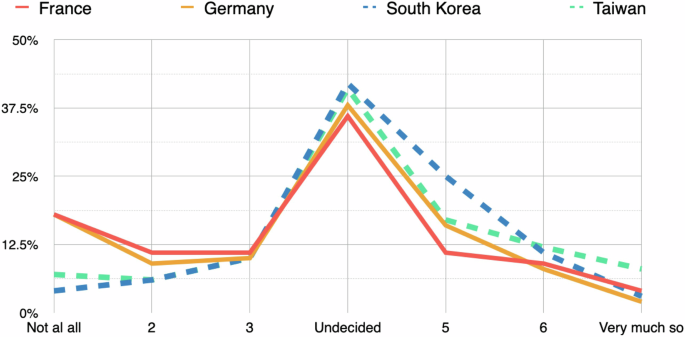

The mean results for change in self-image were slightly below 4 (the indicator of “undecided”) for France and Germany (M = 3.54; SD = 1.68 and M = 3.59; SD = 1.6). South Korea and Taiwan had a mean of 4.2 (SD = 1.26 and SD = 1.5, respectively). The largest proportion of respondents in each country chose “undecided” to the question whether the awareness of microbiome influenced the image of who they are: 36% in France, 38% in Germany, 42% in South Korea and 41% in Taiwan.

In France ca. 40% of respondents chose scores between 1 and 3, indicating that awareness of microbiome did not affect their self-image. The scores from 5 to 7 (7 indicating strong influence) were chosen by 24% of the participants. In Germany these proportions were 36% and 26%, respectively. Asian countries demonstrated a reversed pattern. In South Korea 20% of participants reported no influence of microbiome awareness on their self-image, whereas 38% reported such influence. For Taiwan these proportions were 23% and 36%, respectively. The proportion of participants highly affected by awareness of HM (scores 6 and 7) ranged between 11% (in Germany) and 19% (in Taiwan). An overview of score distributions is provided in Fig. 2.

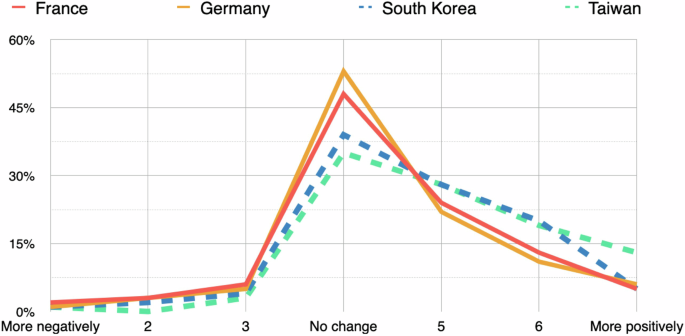

The question on how awareness of HM affected one’s attitude towards microbes and the microbial world resulted in the mean score of 4.48 in France (SD = 1.16), 4.49 in Germany (SD = 1.07), 4.73 in South Korea (SD = 1.12) and 4.99 in Taiwan (SD = 1.19). Many participants reported a positive change. It was largest in Taiwan (61% with scores from 5 to 7 and 32% who scored 6 and 7) and in South Korea (53% and 26%, respectively). These numbers were somewhat lower but still impressive in France (42% and 18%) and in Germany (38% and 17%). The proportion of participants who reported no change was the highest: 48% in France, 53% in Germany, 39% in South Korea and 35% in Taiwan. Some respondents reported a more negative attitude (11% in France, 8% in Germany and South Korea and 4% in Taiwan). An overview of score distributions is provided in Fig. 3.

Demographically, the highest change in one’s self-image was reported by higher educated participants (M = 4.07; SD = 1.5), and by those working in healthcare or life sciences (M = 4.33; SD = 1.67), whereas non-believers reported lower scores (M = 3.55; SD = 1.54). These demographics also reported a more positive view on microorganisms: the mean score for higher educated respondents was 4.85 (SD = 1.11), for healthcare and life science professionals 5.03 (SD = 1.17); it was 4.4 for non-believers 4.4 (SD = 1.13).

Willingness to engage in HM citizen science projects

About half of the survey participants (from 45% in South Korea to 51% in Taiwan) demonstrated some willingness to be involved in research projects where citizens collect and share data on their microbiome to promote public health (overall M = 4.47; SD = 1.66). The mean score was highest among healthcare and life science professionals (M = 5.01; SD = 1.53) and respondents with higher education degree (M = 4.65; SD = 1.59), whereas non-believers showed less interest in doing so (M = 4.18; SD = 1.71).