CNN

—

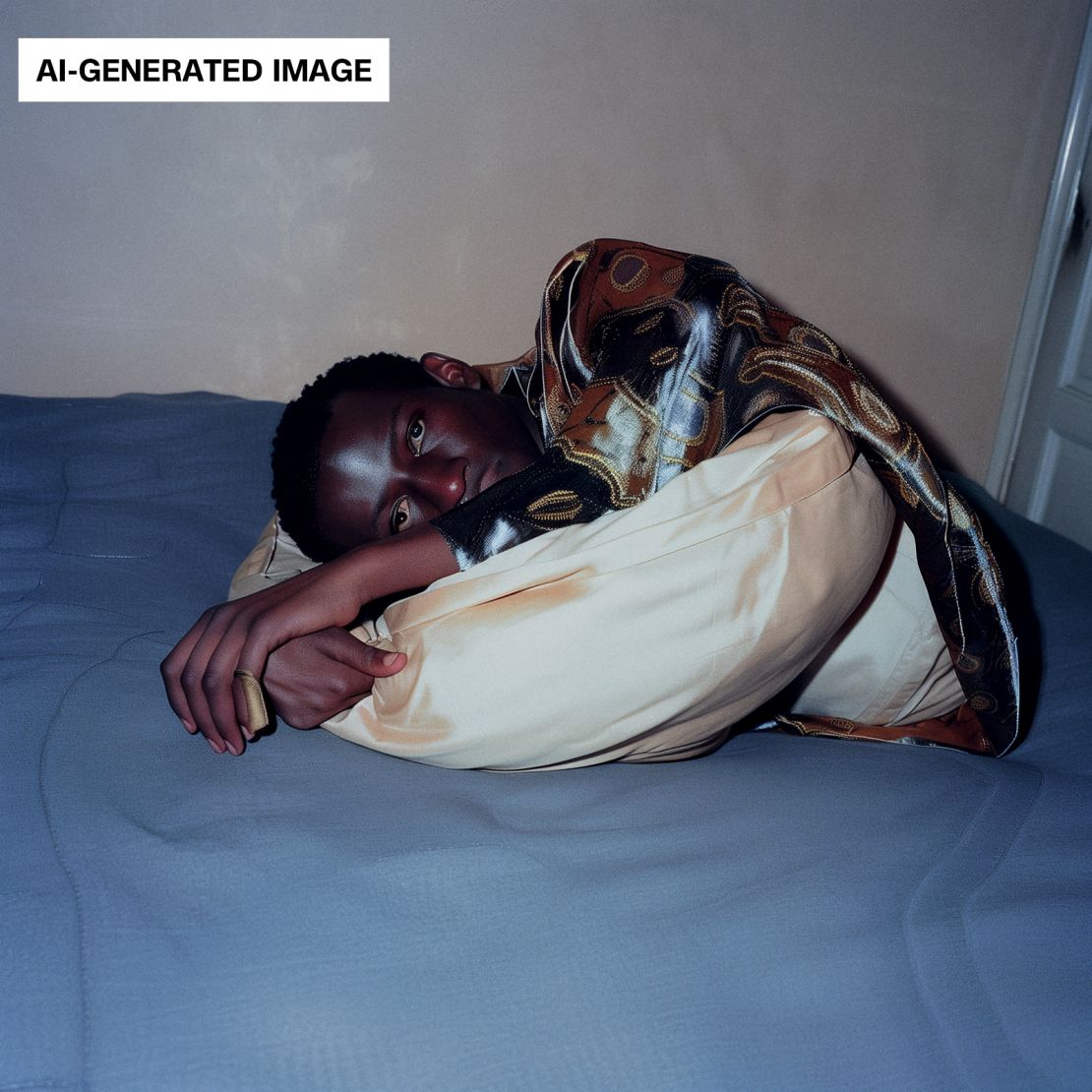

Too many fingers or too many teeth — as generative AI imagery exploded across the internet last year, these bodily mishaps became both a punchline and a tell-tale sign that these photographs weren’t real. Instead, they were a machine’s best-guess at the world through human prompts. The images that went viral were often unnerving: high-flash nostalgic party pictures of grinning models with extra molars, or portraits of a sobbing Steve Harvey sloshing liquor in a pitch-black room.

But over the past two years, the Brooklyn-based photographer and director Charlie Engman has been intentionally leaning into the strangeness of AI photographs, generating eerie images — using the program Midjourney — that feel set in the real world but toy with anatomy and gesture in disquieting ways. In his book “Cursed,” a man in a suit steps knee-deep into a shallow puddle in the morning light, swan wings extending from his shoulders. In another image, a woman stares at a ruddy sculptural bust with her own features that seems to be staring back. Limbs morph and disappear altogether, faces are slick and masklike, and inanimate objects resemble human limbs. People hold animals close and sometimes start to become them, the new forms seemingly evolving or decaying.

“(AI) does things very wrongly,” Engman explained to CNN in a video call. “It has this tertiary relationship to the physical world, where it’s representing a human’s representation of (it). And so it deconstructs physical gestures and human bodies… in just this really raw and sort of a guttural way.”

Sitting with the images can bring on a creeping sense of unease. Some subtly veer from the everyday to the unnatural, like a woman holding a thin blade to her cheek, smiling, eyes locked on the viewer. Others are nightmarish renderings, such as a David Cronenberg-like fetus of both insect and human anatomy.

Through “Cursed,” Engman was looking to strike a kind of “balanced dissonance” that felt like an elaboration of his own photography work, he said.

“What’s desirable, what’s disgusting, what’s beautiful, what’s ugly — you’re forced to confront, on a feelings level, what those criteria are,” he added.

Engman has often played with those tensions across his work. His intensive 15-year collaboration with his mother, “Mom,” probes at the dynamics of both a mother-son and photographer-subject relationship in sometimes uncomfortable ways. Elsewhere, his art direction for the Brooklyn fashion label Collina Strada has seen models both morphing into animals on the runway or barreling down it with unhinged grins.

Like many people, Engman was first introduced to AI through the app Lensa, which allowed people to generate stylized AI self-portraits to share on social media. But after a colleague at Collina Strada showed him his experiments in Midjourney in 2022, Engman was hooked.

“It’s like a slot machine, right — you put in a prompt, and then you get something out. And what you get out is not really that important…there was a naive beginner’s joy that I had with it,” Engman recalled of using Midjourney. “I think I was maybe clinically addicted to it. I was up at 2 am (using it).”

Because of his ongoing work with his mother, Engman seized on the technology as a new form their collaboration could take, training Midjourney with a set of her images. And though his mother does appear sporadically in the book, including as limbless, moth-winged figure, she’s more of an easter egg for those familiar with Engman’s work, than a focal point.

Though “Cursed” does naturally veer into the realm of horror filmmakers, Engman steered clear of visual references and instead began reading texts related to critical disability theory. The questions he found himself raising about the body and ability are reflected in the imagery.

“What are the actual limitations of a body? What is a normative body? What are the limitations of a normative body? When does a body start to move out of the normative frame, and what is the threshold?” he posed. “Those are the things that body horror is also talking about, actually probably in a very similar way.”

Animals feature, too, with swans, dogs and horses making appearances as fully-formed or disassembled suggestions of creatures. Engman returned to them because the way they rendered was beautiful to him, he explained, but they also have a long history of implied symbolism, too.

“They are categorically allegorical animals, so I was able to make poetic conceptual connections between human and non-human,” he said. Because of their use in art, literature and other media, “there’s already an elaborate language for it that people can connect to.”

With the acceleration of AI imaging, the book is already a marker of a time that is fading from view. Photography books from concept to print often come together over years, not months. Engman found the technology was moving faster than the project as multiple new updates rolled out for Midjourney — and jumbled features such as six-fingered hands were becoming obsolete.

“The first images that I made for the project and the last image I made almost couldn’t co-exist… they were almost on two different registers and that is very interesting to me, too,” he said.

“What was so fascinating, and actually was very motivating, is that I was making an out-of-date book. As I’m making the book, it’s already out of sync with what’s happening,” he added.

New AI abilities have generally come in bursts, then pause as processing power catches up and breakthroughs are made. There may be a “ceiling” to this new wave of generative AI imagery in how accurately a computer program can understand and depict the world, Engman acknowledged, and he’s curious, not anxious, about what happens next.

In the future, the context may be lost for “Cursed,” with anomalous generated bodies just a blip in the larger scheme of faithful AI renderings. Or maybe the next gen of AI swerves us even deeper into the uncanny valley in yet unknown and frightening ways. Either way, Engman wants the book to stand on its own.

“There has to be something interesting about the work that’s outside of the technology,” he said. “The technology has to be subservient to the content.”