ANGEL FOSTER has a vision of a patient. “Imagine you’re a 23-year-old woman in rural Texas”, the doctor and public-health researcher says. This patient is pregnant and wants an abortion. For years, she’s been told that it is illegal in her state, with almost no exceptions. But then, with a bit of Googling, “you find out that there’s this group of people in Massachusetts that will send you FDA-approved medications in the mail.” The ordeal will be over in a few days and will cost $5. “It sounds absolutely bananas, right?” she asks “How could it be legal? How could it be safe?”

Yet it is safe and legal. Dr Foster is one of the founders of the Massachusetts Medication Abortion Access Project (the MAP), a telehealth abortion provider outside Boston. It sends between 2,000 and 3,000 packages of abortion pills a month, 95% of them to states where the procedure is banned. Massachusetts is one of eight states that protects abortion providers from criminal and civil litigation, regardless of where pills are sent (see map). Such “shield” laws are legal novelties that have sprung up since 2022, when the Supreme Court overturned Roe v Wade. In the first six months of 2024, there were nearly 10,000 abortions a month under these provisions—10% of all legal abortions in America. That number is probably even higher now. Partly due to telemedicine abortions, Mississippi women—and those in nine other ban states—now have more abortions than before the procedure was outlawed.

The MAP office “looks like an Etsy startup”, Dr Foster observes. Shipping cartons stack up next to Post-its with passwords and old Christmas cards—but open a cabinet and there are hundreds of doses of abortion pills. The post office assumes they are shipping jewellery, mistaking the rattling of pills in bottles for beads. The process is simple: women fill out some online forms (other providers require a phone call) and send $5. Medically, this is fine. Telemedicine abortion is legal in Britain and is safe: a 2024 study published in Nature Medicine found that 99.8% of such abortions in America were not followed by a serious adverse event.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) permits telemedicine abortions only for early pregnancies and doing it at home can be unpleasant—some women worry about the amount of bleeding and go to hospital. Some legal danger remains. Although women are generally not forbidden from ending their own pregnancies (typically laws penalise providers and supporters), a handful have faced charges for related crimes—the most grisly being improper disposal of a corpse. For health-care providers (in some states, midwives and nurse practitioners can also perform abortions) there are risks. “I’m not an activist in general” explains one family doctor in California who does shield-law abortions, “I’m doing this because I can and it’s needed.“ Shield laws prevent extradition from only the shielded state. Because he now avoids leaving California, that doctor is missing the birth of a grandchild.

Anti-abortion activists are incensed by the workaround. In December Ken Paxton, Texas’s attorney-general, filed a civil suit against Maggie Carpenter, a New York doctor, for sending abortion pills into the state. Louisiana followed in January, indicting the same doctor with criminal charges for sending pills to the mother of a pregnant teenager. So far, though, the shields are holding. Kathy Hochul, New York’s governor, has refused to extradite the doctor and courts in the state are not enforcing Texas’ $113,000 penalty. Mr Paxton has promised to press on, claiming that “New York is shredding the constitution.” A challenge in federal court is likely.

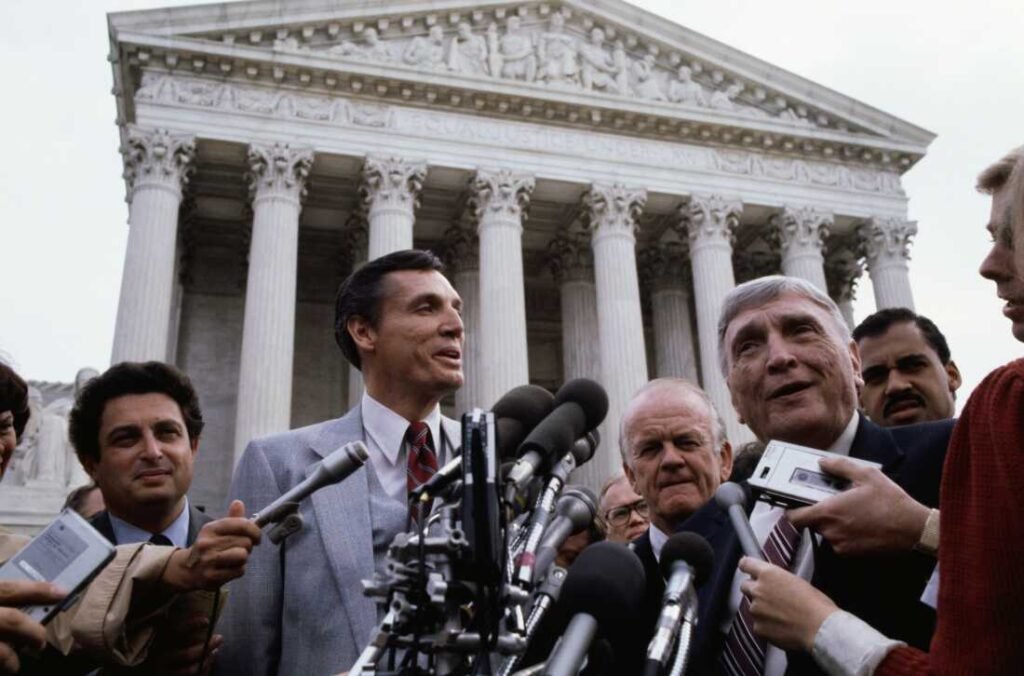

“There’s no patient who’s come forward to say: ‘I was shipped the wrong pills… I’ve suffered these consequences’,” says Rachel Rebouché, a dean of Temple University law school, and one of the architects of shield laws. In a hunt for such harm, lawyers are reportedly looking for would-be fathers to bring a suit. So far the action against Dr Carpenter has simply succeeded in publicising the option, triggering an uptick in the use of abortion pills. The shield laws are “probably going to end up before the Supreme Court, it is just a question of when” says Mary Ziegler, a legal historian.

The constitutional questions are profound. That states respected judgments and co-operated in investigations “was a really strong value and default that crossed partisan lines”, says Ms Ziegler. “Shield laws clearly are undermining that value.” It is possible to imagine their use spreading beyond abortion to cover more things some states ban and others permit, like conversion therapy or psychedelics. Some states already apply them to transgender medicine. “I don’t know how you put that genie back in the bottle” says Thomas Jipping of the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think-tank. “If we can’t agree on the underlying principles that hold the country together, well, then we’re going to have deep, deep problems going forward.” He frets that “the country may well come apart.”

Shield-law advocates say that abortion is special and the laws are unlikely to spread further. A federal law could bring clarification, but any attempts in the current Congress would be blocked by a Senate filibuster. Donald Trump’s administration has some options to limit shield laws: the FDA could require mifepristone, one of the medicines used in abortion, to be received in person. Medication abortions can be done without those pills, but it is less effective and more painful. The Justice Department could also attempt to enforce the Comstock Act, an archaic anti-obscenity law, that, among other things, bans the posting of abortifacients. The president has said abortion laws should be left to states to decide. But he probably did not envisage this.