Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is a vice-president at Dimensional Fund Advisors and co-host of the “Informed Investor” podcast

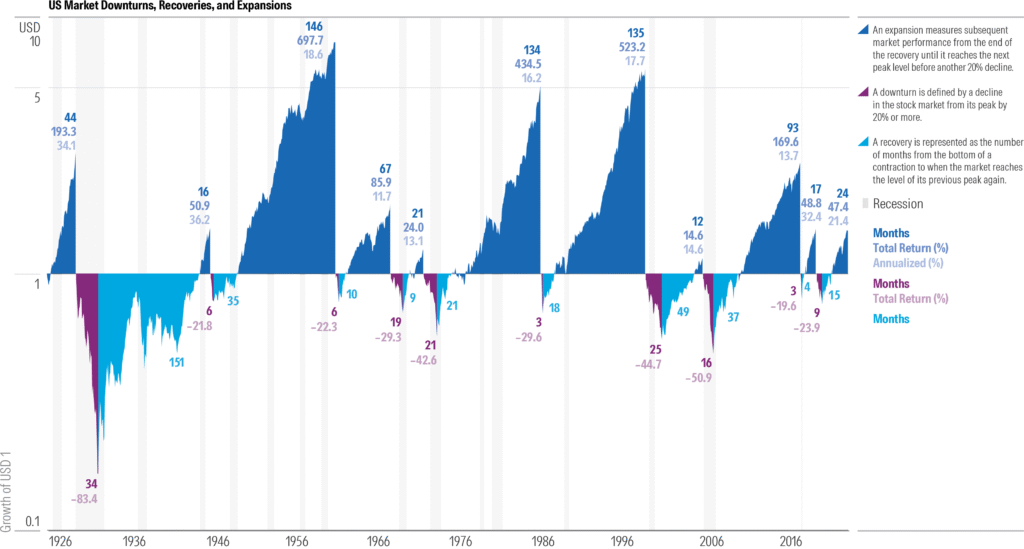

The rationale for investing in the stocks of small companies is well established through empirical record, academic literature and decades of practical asset allocation. Over the past century, small caps have outperformed large caps by roughly 1.5 percentage points annually.

The recent outperformance of large companies has obscured the benefits for long-term investors who allocate some of their portfolio to US and global small caps. Popular misguided narratives about the state of small caps have not helped.

Since small caps represent a meaningful part of the global market — about 10 per cent of the US by market capitalisation — they belong in a diversified portfolio. These are companies from a variety of sectors and many have the potential for significant returns. After all, firms such as Nvidia were start-ups before they were giants.

Those worried about overexposure to the currently high-priced US market might find small-cap valuations compelling. While the aggregate price to trailing earnings multiple for US large caps has grown to more than 30 times — nearly double the average since 1963 of 17.6 — the ratio for US small-cap stocks is just 16.4.

Spreading investment to small caps helps lessen the exposure investors have to top stocks such as the Magnificent Seven, which now account for more than 35 per cent of the weight of the S&P 500 index.

And there are good reasons to question the aberrational recent returns of US large caps.

Large caps beat small caps by more than 8 percentage points annualised (19.7 per cent vs 11.6 per cent, respectively) over the three years to June 30 2025, according to Dimensional indices. But historical context for those two returns is important.

The S&P 500 index’s return over that stretch was nearly double its long-run average since June 1927. Contrast that with US small caps, where returns hewed much more closely to their long-run average of 11.6 per cent for three years and 11.9 per cent since 1927.

Expecting a continuation of large-cap returns well in excess of the historical norm is a bet on further unexpected success stories for these firms.

As for small caps, much postmortem effort has been devoted to uncovering causes why they have trailed bigger peers in recent years. These have revolved around the idea of a “new normal” incorporating everything from the impact of private equity (resulting in fewer IPOs or older market debutants) to technology upheaval (mainly AI).

The volatility of stock return data makes it hard to identify trends like these in market pricing. But one data point makes a compelling case that a key mechanism responsible for the premium for investing in smaller caps historically is alive and well.

Migration, when firms grow into the mid or large caps, has been a key driver of the long-run outperformance of small stocks. The good news for investors is that this migration has been occurring at roughly the same frequency even in recent years — 11 per cent in the last 10 years and 10.1 per cent since 1926.

It’s also worth noting that the data on the size premium has been rosier outside the US. In non-US developed markets, small caps have been about even with large caps over the past three years and have outperformed over the past half-decade.

Some of the concern over the small-cap asset class has focused on deteriorating financials for firms of this size. These concerns are not unfounded but pertain primarily to one specific subset of the small-cap market — in particular, stocks with high valuations and low profitability. You don’t need an economics degree to know that this combination of characteristics is bad for expected returns.

Excluding low-profitability growth stocks — the bottom quartile of companies ranked by operating profits as a percentage of net assets or book equity — substantially improves expected returns from small caps (15.17 per cent annualised for US equities since 1975 compared to 13.95).

The largest and most successful companies of today were small caps once upon a time. A broadly diversified allocation to the small-cap market can help long-term investors capture future winners from today’s smaller firms.