How might one begin to describe the year in U.S.-China relations? A roller coaster? A tightrope walk? A boxing match? A stormy sea? A high-stakes game of chess, tug-of-war, or poker?

Whatever it was, it sure kept the staff at Foreign Policy on our toes.

U.S. President Donald Trump returned to office in January promising to overhaul the United States’ trade system, and he wasted no time in getting to work. In early February, Trump imposed a new 10 percent tariff on all Chinese goods, which kicked off a monthslong cycle of escalations, retaliations, abatements, pauses, extensions, and negotiations.

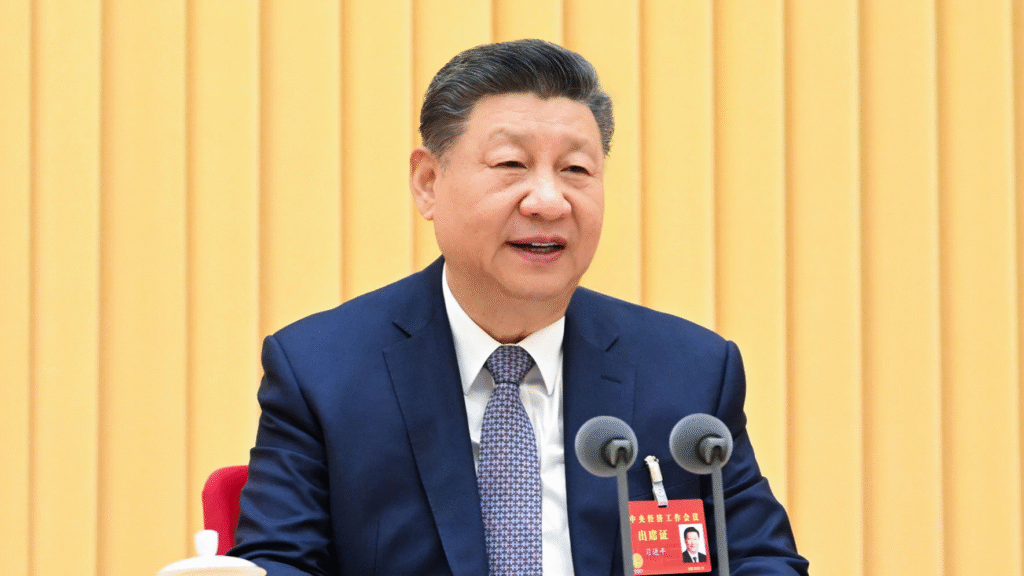

Then, in late October, Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping held a momentous face-to-face meeting in Busan, South Korea—their first since 2019—and agreed to a one-year pause on further trade hostilities. The two stopped short of a full agreement but dialed back some of their harshest mutual countermeasures.

Though trade ties have stabilized for now, this year’s saga has exposed just how much leverage China has over the United States, especially when it comes to agriculture and rare earths. And in areas where the United States has the upper hand, such as artificial intelligence (AI), China has redoubled its push for self-reliance—accelerating domestic semiconductor chip design and manufacturing and investing heavily in its own AI industry.

In other areas, the Trump administration proved willing to sabotage or outright cede U.S. dominance. In May, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio pledged to aggressively revoke the visas of Chinese students, who contribute billions of dollars to the U.S. economy and are the backbone of research and technology innovation. Trump later reversed course, but serious damage to enrollment and long-term trust had already been done.

The Trump administration’s swift and dramatic withdrawal from global leadership has created many openings for China to seize if it so chooses. Although China is less likely to fill the foreign aid lacuna created by the dismantling of the U.S. Agency for International Development, it has already raced ahead to become the world’s green energy superpower—a reality that was on stark display at November’s United Nations climate summit in Brazil. The United States was notably absent from the event.

Meanwhile, U.S.-China tensions endured on the military front. The Taiwan and the South China Sea flash points remained as volatile as ever, and China’s assertiveness continued to test the limits of U.S. deterrence and its strained alliances in the Indo-Pacific. One of the year’s more memorable moments came in September, when Xi showed off both China’s new weapons and its old geopolitical allies at a military parade in Beijing, with Russian President Vladimir Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un in attendance.

It won’t be long before Xi gives a tour of the Chinese capital to Trump, who agreed in a recent phone call to visit Beijing in April. Between now and then, it is anyone’s guess whether the United States and China will follow through with their Busan commitments, or if relations will deteriorate once again. (Or if, at long last, we’ll finally see a real sale or ban of TikTok in the United States.)

The following pieces examine how this year of chaos might shape decision-makers’ approaches to the U.S.-China relationship going forward.

1. Did Biden Get China Right?

By Lili Pike, Feb. 6

It may seem indulgent to read a retrospective of former U.S. President Joe Biden’s legacy, given all that his successor has done to dismantle it. But this piece is well worth your time.

Informed by interviews with more than 20 former and current U.S. officials as well as China experts from across the political spectrum, former FP staff writer Lili Pike writes what may be the definitive account of Biden’s China policy.

As Biden entered his final weeks in office, the administration declared its “invest, align, compete” strategy to be triumphant. Since picking up the baton, Trump has doubled down on certain components of this approach. But today, both sides of the U.S. political spectrum are debating where to go from here.

“On the right, many China hawks say that Biden simply didn’t go far enough,” Pike writes. “At the same time, dissenters on the left argue that—in the fog of competition—Washington has lost sight of the urgency of climate change and other long-term U.S. interests.” In this fog, the two superpowers may be stumbling toward crisis.

This deep dive is a welcome—and frankly, necessary—level set for understanding the new contours of debate within the halls of Washington.

2. Why Beijing Thinks It Can Beat Trump

By Scott Kennedy, April 10

Fast-forward a few months: Trade tensions had escalated, and U.S. tariffs were beginning to bite. On April 4, China hit back hard with retaliatory tariffs, which elicited the following response from Trump on Truth Social: “CHINA PLAYED IT WRONG, THEY PANICKED—THE ONE THING THEY CANNOT AFFORD TO DO!” Trump seemed to think that China would cave because of its ongoing economic challenges and the importance of U.S. products and markets.

In a revealing piece, Scott Kennedy, a senior advisor at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, explains how Trump’s erratic policies; domestic institutional upheaval; and attacks on science, media, and multilateralism have ironically strengthened China’s resolve and its relative standing both at home and abroad. “[M]y sense is that the Chinese government believes it has no choice but to stand its ground,” Kennedy writes.

3. A Bull in the China Policy Shop

By Lili Pike, July 2

“In Trump’s first term, his China advisors successfully pushed to make competition with China a central U.S. mandate,” Pike wrote in July. But in his second term, “shoot-from-the-hip decision-making—from the rapid swings in trade policy to sweeping personnel cuts—has dominated and is complicating the U.S. mission to outcompete China.”

This reported deep dive examines how Trump’s often-diverted foreign-policy attention has hampered his ability to pursue strategic gains. Though officials insist that Trump’s intent is clear, the administration’s massive personnel cuts, foreign aid freezes, and the dismantling of key programs and research initiatives have weakened the institutional capacity needed to coordinate Washington’s China policy.

4. How Great-Power Rivalry Hurts Ordinary Americans

By Van Jackson and Michael Brenes, Jan. 31

Factory workers form a picket line outside an auto plant in Louisville, Kentucky, on Oct. 14, 2023.Michael Swensen/Getty Images

As the year unfolded, the repercussions of the U.S.-China rivalry became increasingly visible in the lives of ordinary people.

In an excerpt from their newest book, authors Van Jackson and Michael Brenes argue that Biden’s “new Washington consensus” repeated many of the mistakes of neoliberalism by framing its investments in the U.S. industrial base as a tool to fight the hyped-up national security threat of China. The result is an economy optimized for military primacy, not shared prosperity: It funnels benefits to tech elites while the working class faces stagnant wages, soaring costs, and shrinking social mobility.

The authors’ bottom line is blunt: “Great-power rivalry with China has helped concentrate wealth in the hands of a few, rather than creating a healthy economy,” they write. “It has weakened the welfare state and stymied economic democracy”—trends that the authors say might worsen as the Trump administration continues to compete with China.

5. The United States Is Moving Through the Stages of Grief Over China’s Rise

By Robert A. Manning, Nov. 25

Robert A. Manning, a distinguished fellow with the Strategic Foresight Hub at the Stimson Center, argues that the October Trump-Xi agreement wasn’t just a brief trade truce but a shift in Washington’s attitude toward Beijing.

Using the five stages of grief as a template, he writes that as China’s economic, military, and technological power has grown, the United States’ denial and anger have given way to a bargaining approach in which differences have to be managed with some sense of pragmatism. “Perhaps the biggest takeaway of the meeting was a mutual commitment to a continuing process of dialogue to manage implementation of the deal and, more broadly, the bilateral relationship,” Manning writes.

Though the final stage of grief, acceptance, is still well over the horizon—and depression may await the next crisis—for now, the United States and China appear to have found a more stable, if uneasy, modus vivendi.