By Ka Sing Chan

Made in China 2025 is “very insulting”, then-U.S. President Donald Trump complained in 2018, because it “means in 2025, [the country is] going to take over, economically, the world…that’s not happening”. Launched a decade ago, Beijing’s 10-year masterplan laid out sweeping goals across aviation, robotics and other sectors aimed at transforming the world’s second largest economy into a “manufacturing superpower”. But the industrial blueprint drew intense backlash from Washington and Brussels, which accused China of trying to displace Western businesses unfairly. As Made in China 2025 draws to a close, its successor will reshape global trade over the next few years – and spark even fiercer pushback.

The U.S. leader’s comments at the time underscored the fallout of President Xi Jinping’s grand ambitions. Beijing’s alleged use of state subsidies, preferential treatment of domestic companies, forced technological transfers and other tactics formed a major justification of Washington’s first trade war with China, as well as for sweeping sanctions on telecommunications equipment makers Huawei and ZTE 000063.

Though Chinese officials quietly dropped mentions of Made in China 2025 from policy documents, domestic firms led by private-sector champions like Huawei as well as state-backed giants all stepped up. A U.S. government report published in November found that across the 10 strategic industries identified in Made in China 2025, the country has “met or exceeded many of the very ambitious global market share, local sourcing and technological development targets”.

Battery-powered and hybrid vehicles, for example, are a notable success. Beijing targeted annual production from its automakers of 3 million units by 2025; in 2021, the industry, led by the $117 billion BYD 002594, churned out 3.5 million vehicles. High-end medical devices, ships and space equipment scored similar wins.

By 2023, China’s share of global manufacturing as measured by value hit 28.8%, up from 25.9% in 2015, according to the same U.S. report. In the Made in China 2025 industries, the People’s Republic accounted for nearly one-quarter of global growth in exports in the eight years since the plan was launched, capturing 20% of exports by 2023.

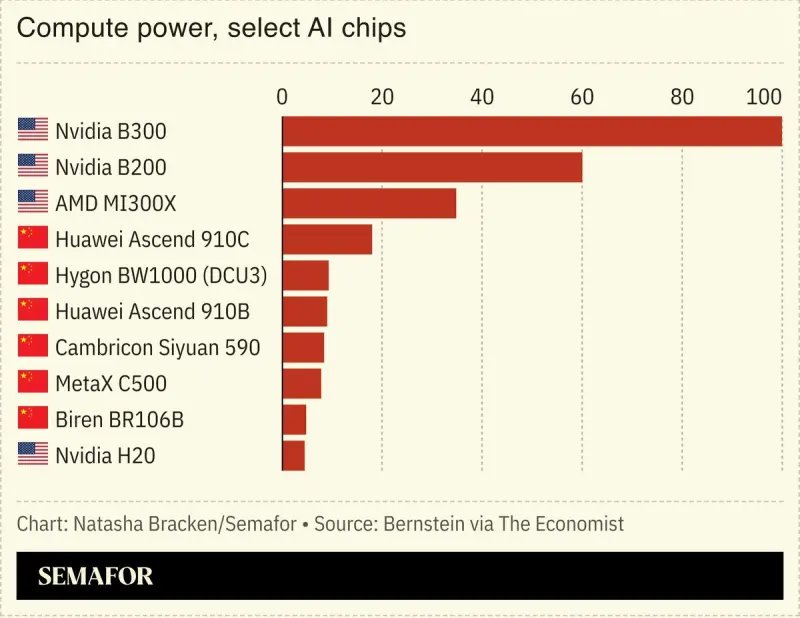

These gains stand out, even if the country has fallen short in critical areas like semiconductors and aviation. Western governments today are floundering to bring back strategic manufacturing sectors and supply chains from shipbuilding to critical minerals.

Against this backdrop, all eyes are on China’s next economic blueprint. Indeed, a Made in China 2035 plan is probably already underway, though given its predecessor’s controversy, Beijing is keeping its masterplan under wraps. Yet under Xi’s political slogan of “new productive forces”, which refers to the country’s next growth drivers, planners have already spelled out industrial targets in various planning documents and directives.

In October, for example, the central government released its official recommendations for the 15th Five-Year Plan, which will run from 2026 to 2030. Similar to Made in China 2025, industries spanning artificial intelligence, clean energy, 6G telecommunications and quantum computing play a central role, with the ultimate aim of “achieving socialist modernisation by 2035″.

For Xi, the stakes look higher than in the past years. Economic planners in Beijing have noted the recent breakthroughs in AI and other tech, as well as escalating geopolitical and economic rivalries, will bring about momentous upheaval “not seen in a decade”. Moreover, the Chinese leader has a long-term vision to double the country’s nominal GDP in 2035, from 2020 levels, to $28 trillion. That implies annual growth of about 4% over the next decade.

That looks possible, but only with booming exports. Earlier this month, analysts at Goldman Sachs hiked up their China forecasts. They now expect the country’s real export growth to increase to between 5% and 6% annually for the next few years, up from a previous forecast of between 2% and 3% in what the analysts term “China Shock 2.0”. This will exacerbate global trade tensions, already made worse by Trump’s tariffs. Economies that will be most negatively impacted include Germany, Central and Eastern Europe and Mexico, Goldman reckons.

Moreover, with U.S. consumers essentially off limits, many Chinese manufacturers are accelerating efforts to crack other markets. Despite the European Commission imposing tariffs of as much as 45% on battery-electric vehicles last year, Chinese automakers have nearly doubled sales in the bloc so far in 2025.

China’s manufacturing focus can also worsen economic imbalances at home. Household consumption in the People’s Republic lags global averages by about 20 percentage points of GDP, while debt-driven investment is roughly double. That has resulted in overcapacity across many industries including electric vehicles and steelmaking.

Combined with weak demand, falling property prices and slowing wage growth, deflation is setting in. The producer price index has declined for 37 consecutive months. Analysts at Morgan Stanley reckon the GDP deflator – the broadest measure of prices across goods and services – will remain negative for 2026. A Japan-style deflationary spiral will add fuel for critics who have long called for a more consumption-driven economy.

Beijing appears to be well-attuned to these concerns. In addition to tech-driven growth, authorities have also been talking up “the need to vigorously boost consumption”. The next five-year plan will also have a target of “significantly” raising the percentage of household consumption of GDP, a top official said in October, though no details were given.

Yet any meaningful shift in consumption would mean a reduction in the share of the economy absorbed by manufacturing. Given the centrality of high-tech industries and exports in Xi’s plans, such a shift seems unlikely. China’s next economic blueprint will rattle global and domestic markets.